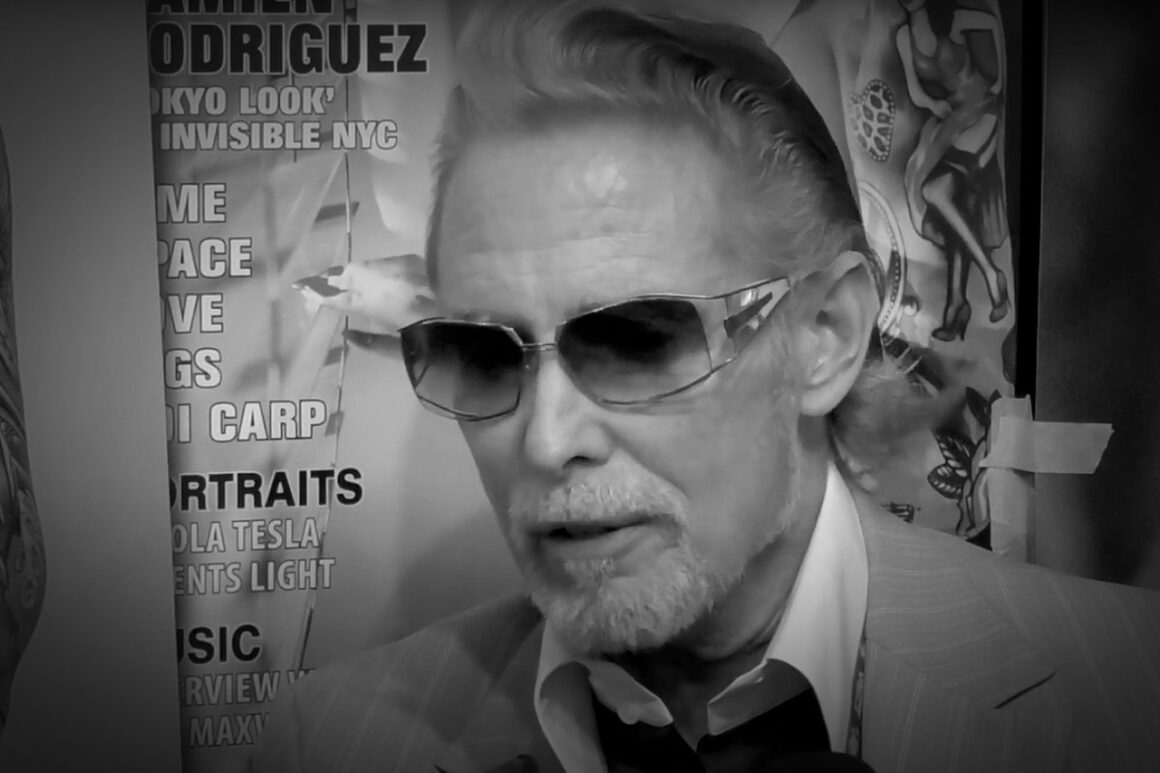

Stefano Bessoni is Roman born and bred: director, painter, illustrator, photographer, teacher and much more, he is an eclectic character and finds all manner of means to drag us into his dark, fascinating world where he reveals all of his knowledge in the scientific and artistic fields.

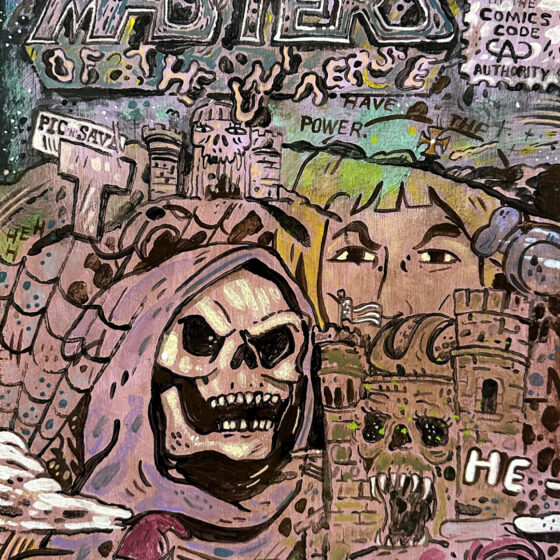

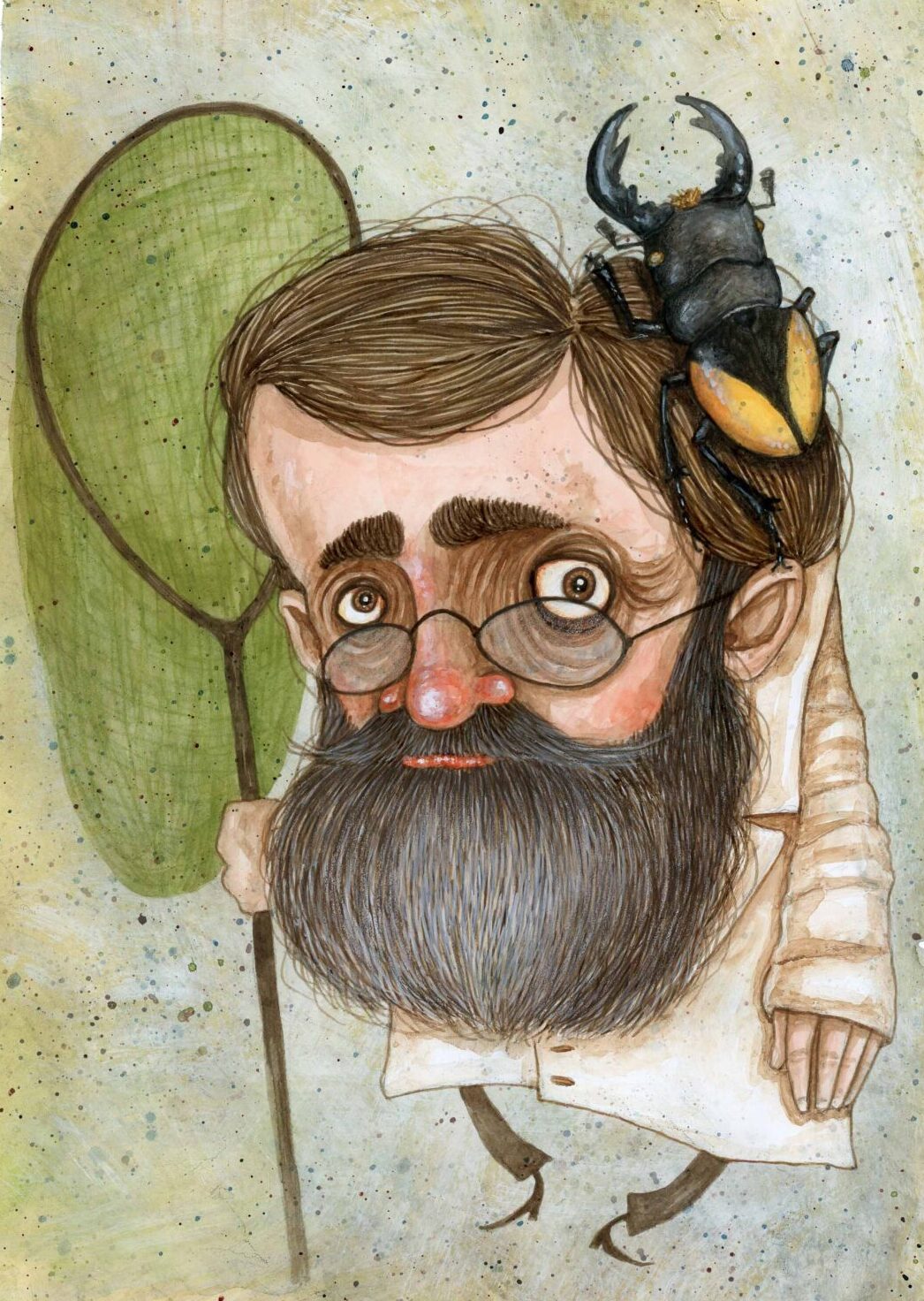

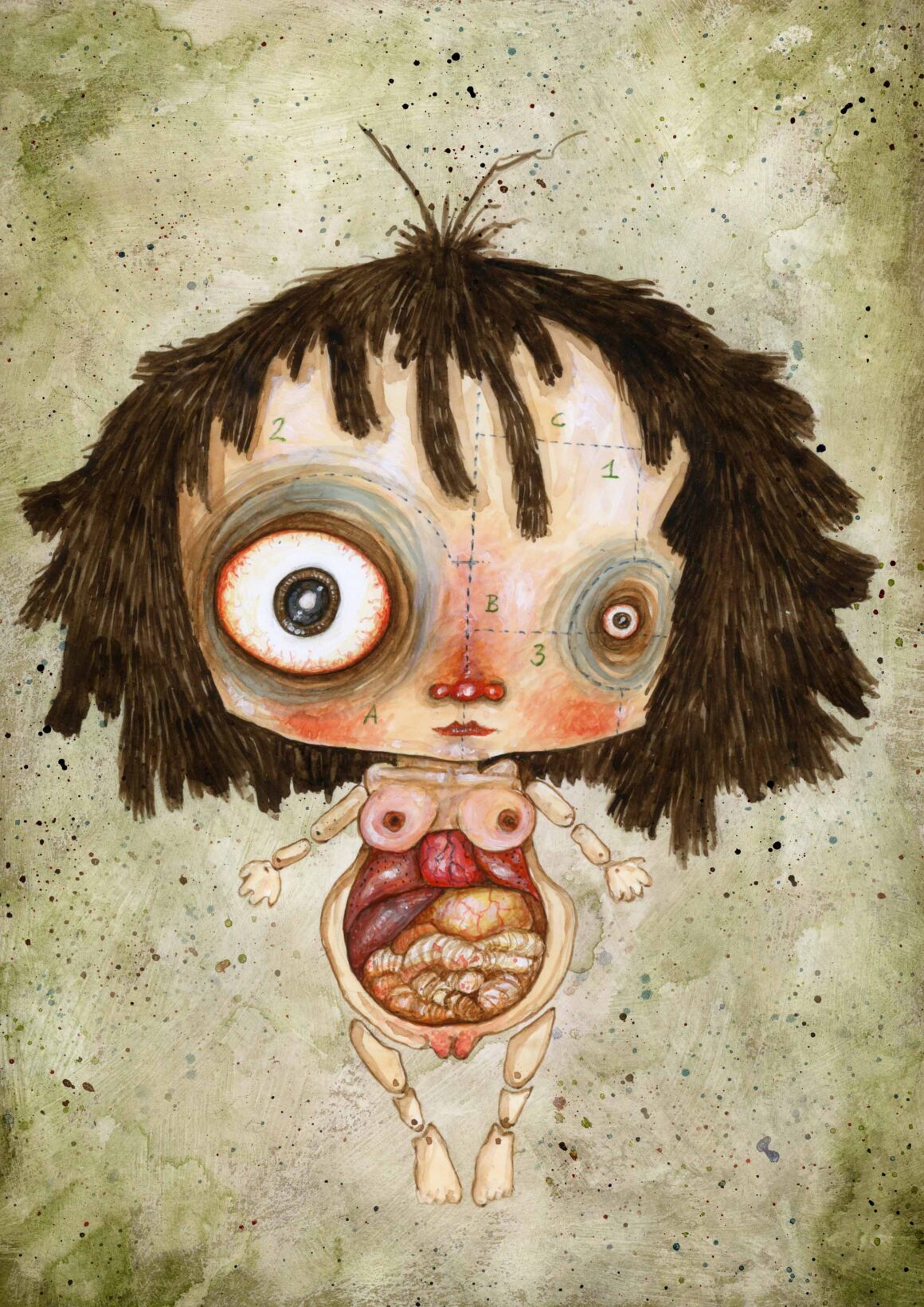

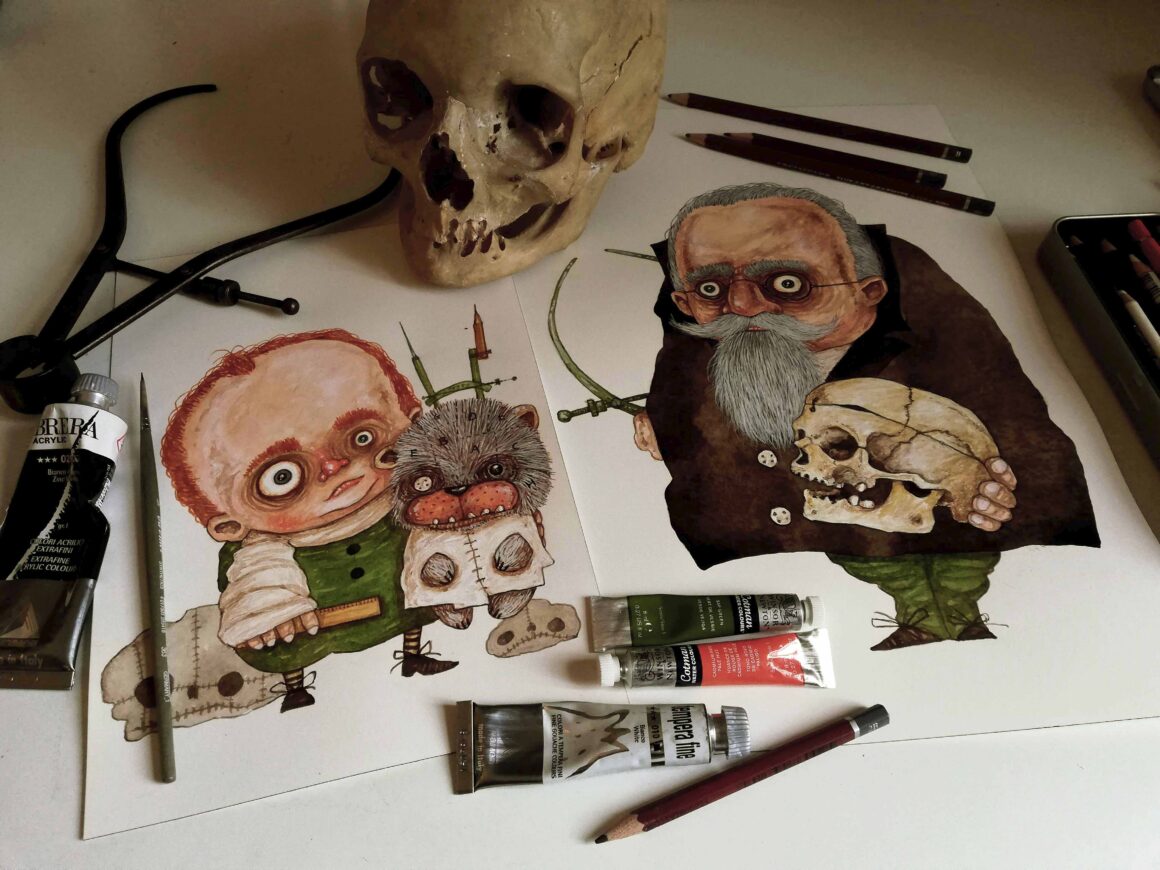

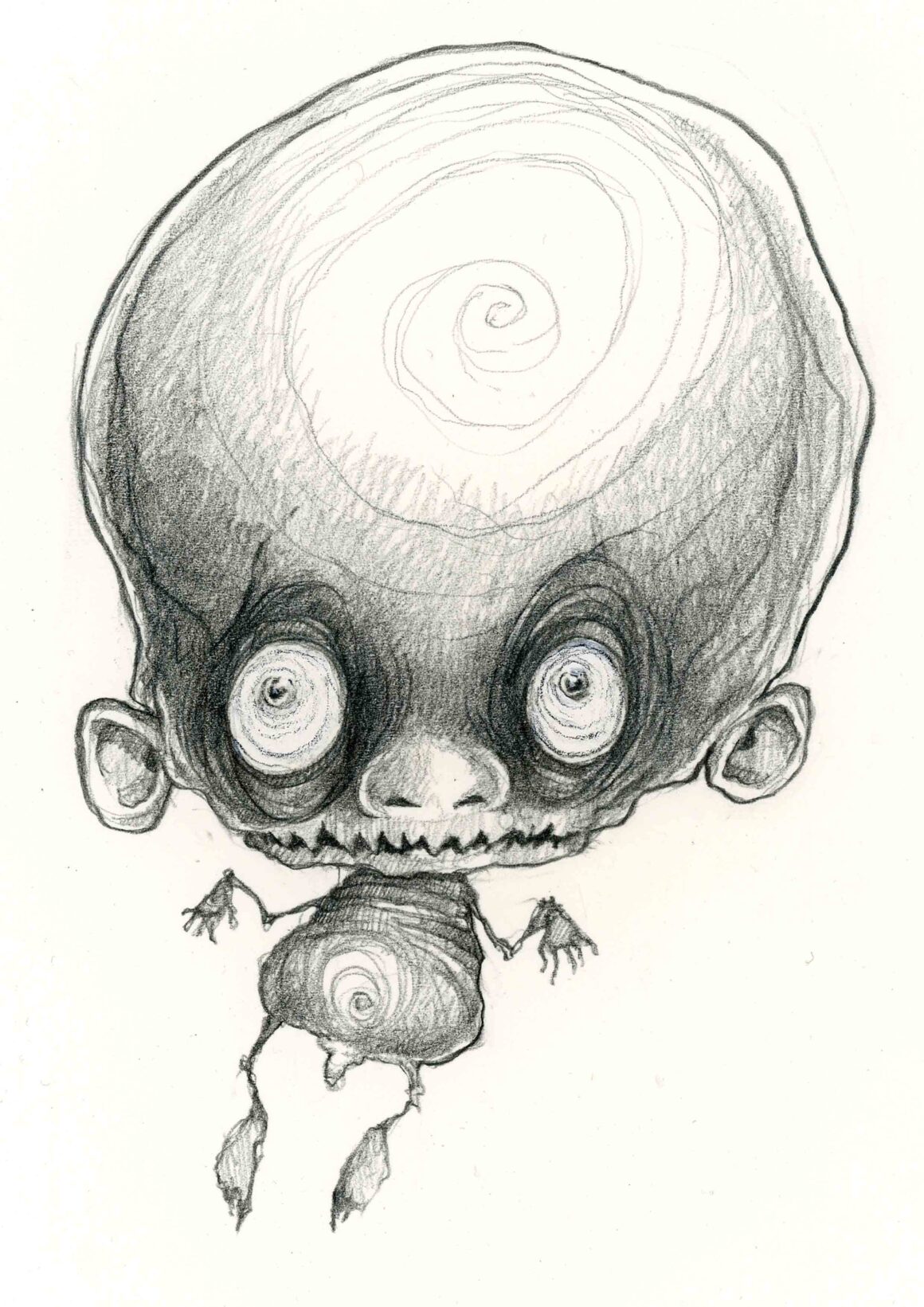

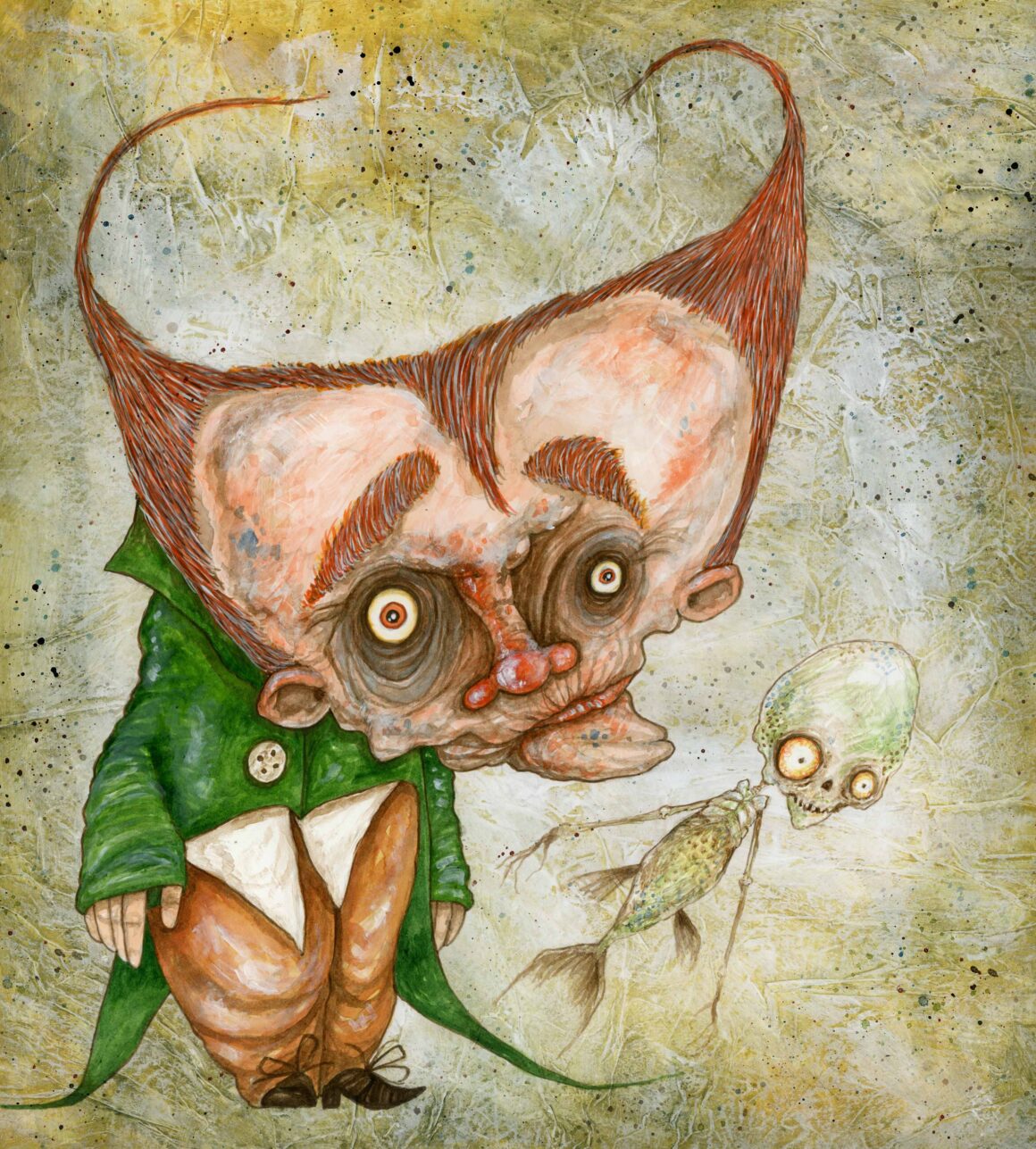

Since the end of the 1980s he has worked on a number of experimental films, attracting the attention of critics and receiving awards in Italy and abroad. He can boast prestigious collaborations like that with the great Pupi Avati, and he is no less active as a painter and illustrator, involved in publishing and ever present at numerous exhibitions in those galleries which specialise in contemporary surrealism. His style is unmistakable, as entomologist, lover of the macabre, decadent and the concept of wunderkammer, a collector of disturbing curios, and all of this can be clearly seen in all his work, whether it be film with flesh and blood actors or stop-motion animation, books written and illustrated by himself or paintings displayed around the world, the style is his, utterly unmistakable. So let’s go and find out a little bit more about this multi-faceted Roman artist.

Hi Stefano and thanks for being here with me to talk to the public of Tattoo Life…

Hi Claudia, and thanks to you!

When we are dealing with an artist who exposes his inner imagination through so many expressive media and in such a detailed manner we just have to wonder who was Stefano as a child? What sort of a childhood did he have? Where did his predilection for insects, dead things and all those things which might revolt or frighten another child actually begin?

“When I was a small I dreamed of being a grave-digger when I grew up, but I didn’t succeed in that so I became a director”… Even though this was something I just scribbled beside a self-portrait of me as a child – and has got around pretty much everywhere, feeding the idea that I am some sort of weirdo – my childhood was perfectly normal, full of curiosity, hobbies and interests, things I think are perfectly normal for any child. Maybe my inclinations seemed a bit weird to adults or my peers, obsessed with football, figurines and superheroes, and dreams of becoming an astronaut or formula one driver.

I liked insects, skeletons and horror films, my hero was Darwin and I hated playing football, couldn’t stand footballers and the fans who were supporters of one team or the other. I devoured the documentaries of Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Bruno Vailati, programmes on the BBC, in particular Life on Earth with David Attenborough, and I watched repeats of Universal’s monster movies: Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Creature from the Black Lagoon. In those days they would broadcast them every day at all hours on private channels like Teletevere.

I would sit down in front of this crappy black and white tv set and get really enjoy them.

Then I’d go and make the characters with play dough and dream up all sorts of improbable homemade remakes, filming with my dad’s old 8 mm which I now treasure as one of the many pieces in my wunderkammer… in there with skulls, dried up animals, puppets and all kinds of objects. Where my inclinations came from I simply don’t know. They were just there and I followed them.

In your biography it says that before you enrolled at the academy of fine art in Rome you studied zoology and biology: to what extent would you say that your predilection for the macabre is rooted in your scientific studies and then blossomed in your more recent artistic expression?

Yes there was a moment, and it lasted quite a few years, when I drifted off in the direction of scientific studies. I completed the first years of Biological Sciences, not without some trouble, seeing as how I was coming from an art school background. Even back in high school I had already developed an interest in entomology and subsequently mammal zoology, especially chiropters. At university I had enrolled as a student in the faculty of Zoology at la Sapienza and was heading down the road to becoming a researcher and scientific illustrator. Then I dropped out. Not because I didn’t like it, but because I was so hopeless at mathematics, physics and chemistry. Never in a million years would I have managed to pass those exams and graduate.

The only thing I was fairly good at was drawing and studying insects and other animals. I was also really into anatomy, museum conservation and the preparation of pathological specimens. I would happily wallow in formaldehyde, I loved the poisonous perfume of paradichlorobenzene and I drawn in the most peculiar way to entomological drying racks, boxes and pins of every size. I said I drifted off in that direction, but in reality it was a real education. As a fallback, or rather to escape from impossible studies and take time to sort myself out, I enrolled at the Academy of Fine Art.

What was your first ever experience with film-making? How do you feel about it looking back?

I made my first short during my time at the Academy for the exam of film direction. They chose me as an actor, and I was forced into it by the teacher so I had to accept. It was a lame experience to say the least and I am painfully embarrassed when I think back on it. Luckily it was a magnetic recording, awful quality, in beta-max and there is no trace of it anywhere today. Or at least I hope not.

What was it like to work with Pupi Avati? What did you work on together? Can you tell us about your experience, maybe tell us some stories about that time?

Working with Pupi Avati was a watershed moment for me. For years I had been working for a television production company as a video operator, cameraman and technician and, when he called me to collaborate with him, I had to make an important decision. I was doing alright in that environment, working for RAI and other television networks, for programmes like “Sereno Variabile”, “Detto Tra Noi”, “Linea Verde”. I really wanted to work in cinema, so I would film and edit my shorts which I then presented at all the various festivals and they even won awards. But I left that company and started working with DueA Film, the production company of Antonio and Pupi Avati.

When I spoke with Pupi for the first time, he read my curriculum vitae and said: “You’ve won a lot of medals!” Then, pointing to a shelf behind him full of plaques and trophies, he added: “Me too.” That day I understand a lot of things and the “medals” are still buried somewhere in a dusty box in the total mess at home, which is basically like saying they are lost. Those awards weren’t all that different from a cup won in a fishing competition or a medal in a bowls tournament. Luckily, I realised that feeling satisfied and that you’ve finally made it is the worst thing there is.

I didn’t make films, even those I was convinced that I did, if anything I was just doing some pretentious form of video theatre. I was not a promising author, even though I had the presumption to think that I was. All I was doing was putting together these convoluted film products, by means which were professional and expensive at the time but not up to the job of yielding satisfactory images, fit to be projected onto the big screen. They were so complex, verbose and chock-full of high-sounding concepts that they often managed to fool the bored juries in festivals in godforsaken places no one had ever heard of.

The years with Pupi were important years for me and I learned and understood many thing, full of anecdotes, but I prefer not to tell them and treasure them in my memory. With him I followed all the work on The Knights of the Quest, A Midsummer Night’s Dance and The Heart is Elsewhere. I worked as concept artist, storyboard artist, in the costume department and set design, and was involved in all the stages of digital effects and post-production under the guidance of Alvise, Pupi’s son, who taught me so many things that were so invaluable for my future development.

How did you develop such an interest in stop-motion animation and the desire to make your own?

It was a natural process. A sort of bridge between film-making and illustration. One day I just felt like I would like to give it a try and so I did. In reality I would have like to do animation right from the start, back when I was at the Academy at the end of the 1980s, when I happened to come across Alice by Jan Svankmajer and Street of Crocodiles by the Quay brothers, but I would have had to work with 16 mm film and expensive equipment which I couldn’t afford, so I just let it go. Then, many years later, with the evolution of digital, and the arrival of Dragonframe software, I reconsidered the possibility of experimentation and started making puppets and animating them. My first ever animations are those inserted into the film Krokodyle in 2010.

Our public is obviously composed largely of people with a great love of draughtsmanship. In that regard I would like to quote something that you said “to let off steam” in your 2010 movie Krokodyle – “there are two kinds of directors: those who know how to draw and those who don’t”. Instinctively emotional and provocative as it was, I imagine that this does encapsulate something of what you yourself truly feel. So I would like to ask you precisely what difference you see between these two kinds of visual narrators.

Ok so, I confess, it’s a sort of cinematographic racism of mine. But still, all the directors I like also draw: Tim Burton, Peter Greenaway, Wes Anderson, Terry Gilliam, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Federico Fellini… Drawing, or even just doodling, allows you to speak a different visual language. Ridley Scott, communicates with his collaborators through sketches on crumpled pieces of paper, they call them “Ridleygrams”, these tangles of penstrokes that are almost incomprehensible but then on the screen are transformed into breathtaking sequences.

I like visionary cinema, made up of free, experimental images, without structure, anarchic.

David Lynch’s Eraserhead is the perfect example of what a piece of cinematic work should be, or then there is Peter Greenaway’s ZOO – A Zed & two Noughts or some of the films of Derek Jarman and Ken Russell. Then there’s the cinema of writing, narrative cinema, a way of storytelling that is based on consolidated forms, devices and models, but stale and too often cliché.

In “Imago Mortis” your 2009 feature film for the big screen, you worked with actresses of the calibre of Geraldine Chaplin… If you could make a wish, what great names of contemporary cinema would you like to work with?

I don’t know, there are no big names that immediately come to mind. When I have to deal with casting, I always have a terribly hard time with it, just because I start daydreaming about ideal, unachievable names. For me the main thing is that they resemble my drawings, with disproportionately large heads, big eyes, short little arms and slender legs. For example Elijah Wood, Cristina Ricci, Maria De Medeiros, Hugh O’Conor, Dominique Pinon, Rossy De Palma and even Geraldine Chaplin look quite like some of the characters I dream up. But in the end it is always very hard to find someone like that in a world that is so vulgar, stereotyped, where everything is based on appearance and glossy ideals of beauty, where actors like that are usually relegated to secondary or marginal roles. Then when I make my suggestions to producers they usually shoot them down straight away, falling back on excuses of “bankability” as they say – meaning that the actors I prefer don’t guarantee a huge financial return. I really like Alex Lawther, who I admired for his performance in the series The End of the Fucking World and the film Ghost Stories. If I ever get to make my project that has been dragging out for almost twenty years now, Moths – A story of spectres and insects, I would love for him to play the leading role.

What are the important names in your artistic education? In cinema, painting, but also in literature or music, for example, are there characters you are particularly close to who fed your expressive drive so that it became what we all see and admire now?

My main point of reference is the English filmmaker Peter Greenaway. I started to think of getting into filmmaking after I saw some of his films. Nowadays he goes from painting to theatres, installations, cinema, conceptual art and he continues to be a huge source of inspiration for me. I have assimilated many of his ways of thinking and utterly share the way he understands forms of expression and the contamination of language.

Greenaway insists that you should always trust the work and not the author. I couldn’t agree more.

He says that he will commit suicide when he turns eighty, in 2022, but he’s a provocateur and I’m sure he’ll find a convincing theory to justify putting it off for at least ten years, maybe till ninety-two, so he can celebrate his favourite number, which is also the atomic number of uranium and that of the suitcases of Tulse Luper, his alter ego. I love the ballads of Nick Cave, the scores for movies that he did with Warren Ellis, the music of Michael Nyman, the photography of Joel-Peter Witkin and Roger Ballen, the illustrations of Dusan Kallay, the pathological preparations of Frederik Ruysch, with the clothes and lace sewn by his little daughter Rachel, the taxidermy tableaux of Walter Potter, ancient bestiaries, compendia of anatomy and zoological tomes, fairytales, folktales, the short stories of Franz Kafka and those of Jorge Luis Borges, the Alice of Lewis Carroll and the Pinocchio of Collodi, the Frankenstein of Mary Shelley, the nightmares of Poe and De Maupassant, the visions of Angela Carter… and I could go on for so long. Better stop here, but those are only what comes to mind at the moment, making a list is an onerous and complex undertaking.

Which artistic project over the course of your career do you feel most sentimentally connected to?

The next one.

It was in the year 2000 that you began your career as a teacher. In fact you started teaching directing and illustration and animation in various Art Academies in cities like Rome, Milan, Turin, and so on. Being a teacher, being able to pass on and share your knowledge to aspiring directors and illustrators, how does that make you feel? They say teaching has to be a vocation, so what sort of a relationship do you develop with your students?

I really enjoy teaching. It is something I couldn’t do without now, even though in recent years it has become my main job, because seeing how hard it is to work in a concrete manner and earn from new projects, it is an excellent way of making a living. Explaining the technical and expressive foundations of cinema, illustration and animation allows me to keep in training and fires me up with creative energy which, shut up in a studio, would tend to fade, leading me to lose myself in projections of dire failure. But now I feel the drive to get back to work on a film of my own and to slow down a bit with the reaching work. I think it is a physiological need, and it will recharge me again, so I can go back to teaching with renewed enthusiasm enriched by my experience which I can then pass on.

In Annie Woody Allen said: “Those who can’t do, teach, and those who can’t teach, teach gym.”

I absolutely agree with this statement, and it terrifies me. Students are “strange beasts”, an assorted fauna of a peculiar ethology. As a good zoologist, I have got to know them and how how to deal with them, but there is always the unknown with some new species, so you have to stay on your guard. But all the same, working with them is always stimulating and now it has become a precious integral part of my world.

As an illustrator, you work with independent publishers and you have a prolific production which is always a great success in that field, so would you like to tell us how this all developed?

My work in the field of illustration also started off in a completely spontaneous way, I can’t even really remember how it happened. I have always said that the means of expression used is not what counts, what matters is the content. So, without even noticing, I went from films to books and I hope I will soon be able to cross over again and work on projects that are somewhere between cinema, illustration, books and animation. I’m a firm believer in the cross-contamination of languages, especially nowadays when the opening up of on-line spaces have allowed for the development of territories of diffusion which were unthinkable up until the end of the last century.

I began publishing with #logosedizioni about ten years ago, thanks to Lina Vergara, who noticed my work and came up with the idea for some projects, taking inspiration from screenplays I had written for cinema. Since then I have continued to work for then on an ongoing basis, putting out one or two titles a year. I hope to go on in the long term because this is a publisher that is something different on the Italian scene, with a marvellous catalogue that perfectly matches my style. I have produced some personal visions for #logosedizioni of Alice, The Wizard of Oz, Pinocchio an original story of my own in four volumes called Le scienze inesatte (The Inexact Sciences) and many other books, including manuals on stop-motion and puppet making.

Then I also collaborate with Bakemono Lab, a fantastic independent publishing project which is managed with courage and determination by Valentina Cestra. Their catalogue too is quite original and interesting, with a range of series that go from fiction to cinema and even illustration, with a number of authors of the highest level. For Bakemono Lab I illustrated the first two books in a series of poetic and entertaining entomodramas written by Varla Del Rio: Spoon – 27 giorni da bombo (Spoon – 27 days as a bumblebee) and Krauss nel gabinetto del dottor Caligari (Krauss in the cabinet of Doctor Caligari). And I also told the half-true story of an execution who was afraid of blood at the time of the French Revolution, recounted by Nicola Lucchi which was called Memorie di un boia che amava i fiori (Memoir of an executioner who loved flowers)”. I would really love to start publishing abroad with publishers I admire who I think would be suited to my projects. One of these days I will have to roll up my sleeves and take some concrete steps in this direction.

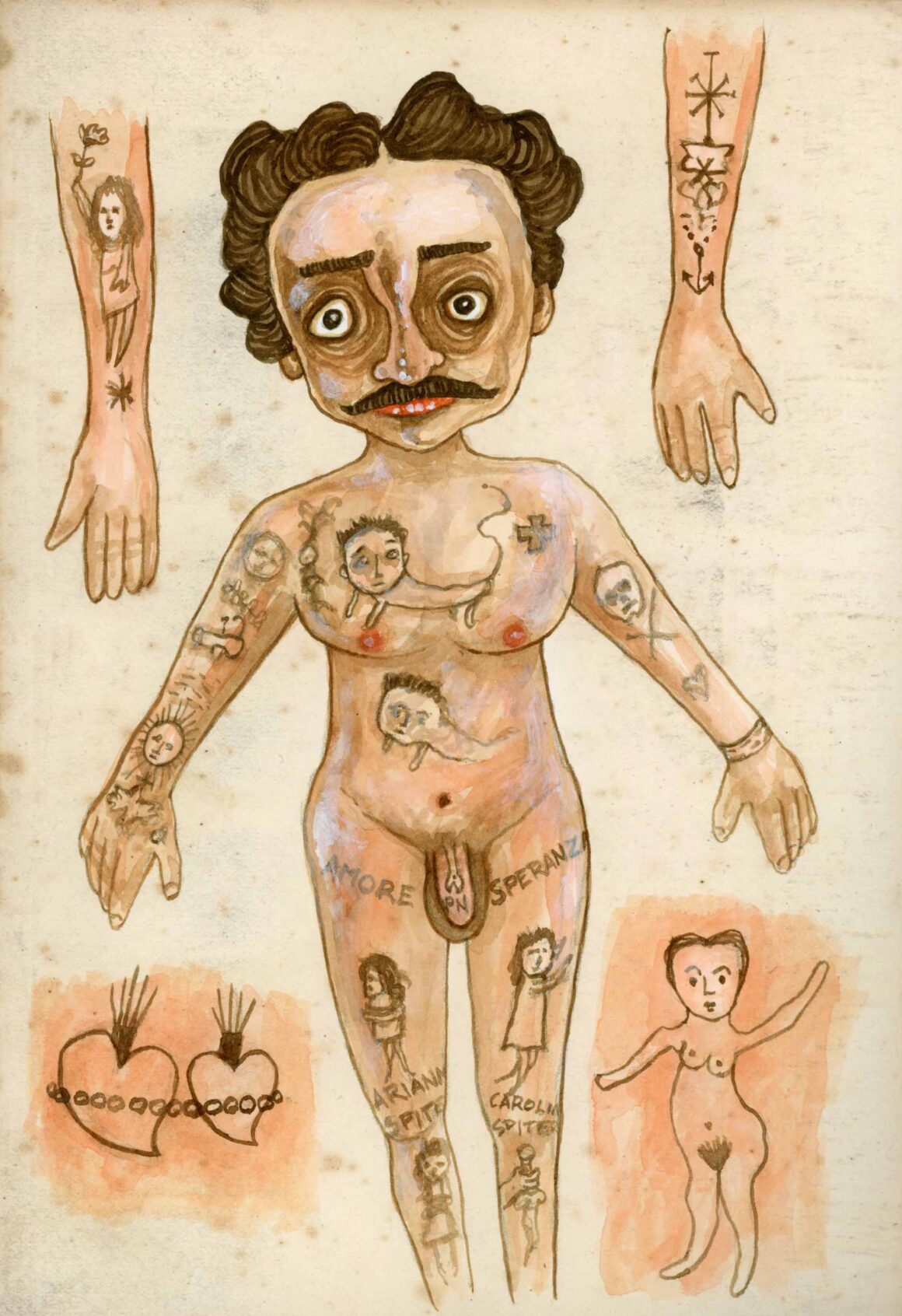

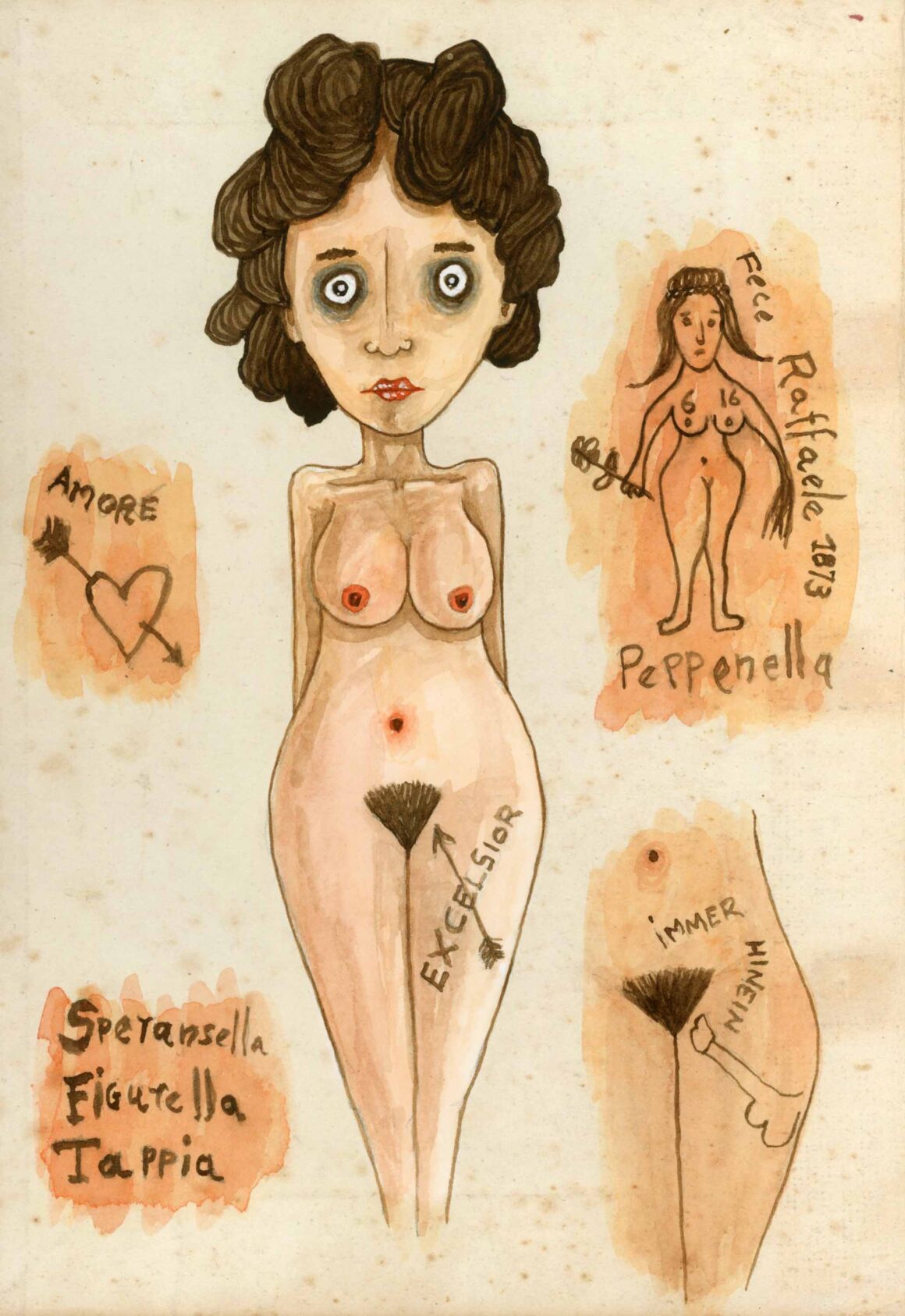

Among the many books you have thought up, written and illustrated that I have had the pleasure to enjoy there is one of the more recent ones which I simply have to mention: Lombroso. In this story – a brief surreal journey through criminology, with your treatment of a character who actually existed – for the first time we find your own characters in the illustrations, with some tattoos to spice things up a little. Can you tell us about your most recent literary and illustrative itinerary? What kind of studies and research did you do on criminal tattoo before you embarked on this project?

Wth Lombroso I wanted to write and illustrate a dark fable set at the time of the unification of Italy, with brigands, madmen, idiots, delinquents, awful diseases, healers, pathologists, mediums and spiritists. The story of Lombroso is the macabre novella of a man devoted to science, who collects the skulls of madmen and criminals and dissects cadavers, in a desperate search for those primitive traits which could have shown the inevitability of the condition of delinquent, a theme he devoted himself to body and soul, teetering on the fine line between genius and madness. His is a story which could have been written by Mary Shelley or Edgar Allan Poe, an adventure so filled with wonders and thrills it seems to good to be true. The life of Cesare Lombroso was dedicated to scientific progress, lulled by the mirage of positivism, which led him to believe that everything could be measured, catalogued and checked.

Today his theories have been confuted, but they still form a basis for the study and important insights into the ethics of science and research methodology.

The point of departure is the confused memories which surface in the head of Cesare Lombroso preserved in formaldehyde. I wanted to create a personal portrait of the father of modern criminology, a controversial figure who is still today the subject of fierce debate. In the story and illustrations I tried to transmit my fascination with the character while at the same time criticising his bigoted, racist, intransigent opinions which over time have provided fertile ground for all manner of discriminations to flourish. My intention was to provide an insight into an incredible story, one that is little known, set in an Italy that is not so far from our own times. As regards the tattoos, I studied and was utterly fascinated by those preserved in formaldehyde, removed from the corpses of prisoners and those traced onto parchment from live subjects.

These flung open the doors of a world previously unknown to me, made up of codes, symbols and signals, indelibly printed onto the skin. It is surprising how tattoo, in Lombroso’s time, was an unhappy link in the evolution of a form of expression, a bridge between tribal culture and modern culture. On criminals it was seen as a sort of “bodily stigmata” which provided the undeniable proof of a sort of atavism, which determined the propensity to delinquency, while in the nobility and high society, or even among the upper echelons of the army hierarchy, it was a symbol of belonging and superiority. Lombroso wrote: “Nothing is more natural than that a custom which is widespread among savages and prehistoric peoples reappear among those classes of humanity who, like the seabed, maintain the same temperature, repeat the same customs, superstitions, even the primitive folk songs, and have in common with these the same violence of passion, the same turbid sensuality, the same puerile vanity, the sloth, and in the prostitutes, the nudity, which in savages are the incentives to such strange behaviour”.

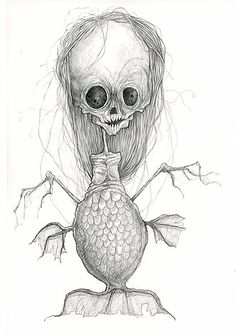

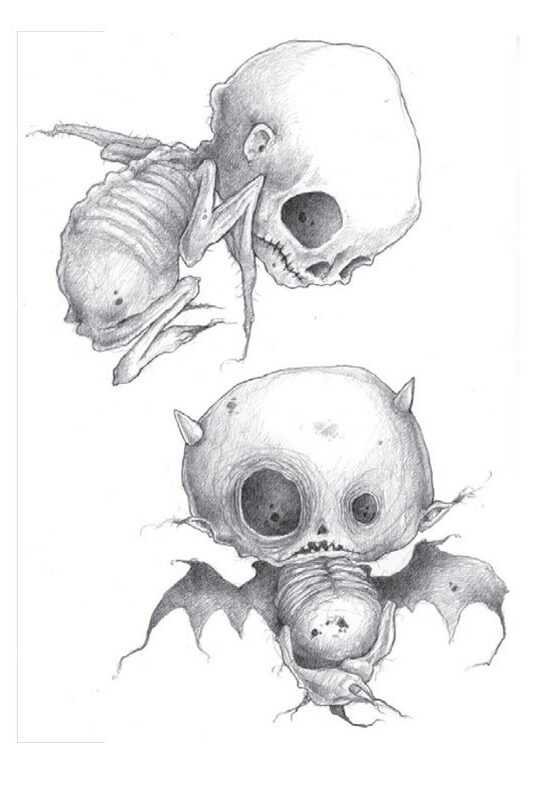

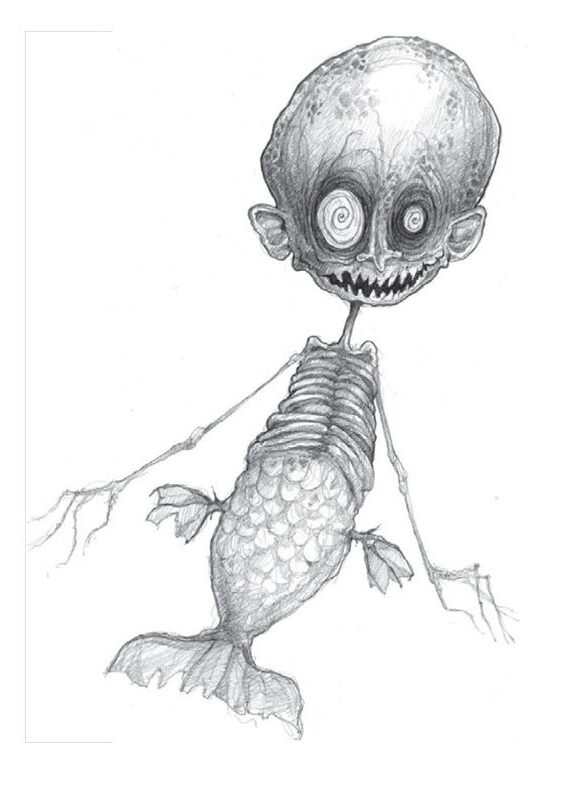

Speaking of tattoo: your characters – from the puppets created for stop-motion to those for the printed page – have often turned into inspiration for tattoo lovers. So we can find a number of your fans who have decided to get tattoos of some of your creatures. How do you feel about this? What does it feel like to see your drawings indelibly inked on someone’s skin? And how do you feel about your art being reproduced by another artist?

If whoever has had one of my subjects tattooed is happy, well then good for him. But I am not all that happy about it and I feel that the original concept is always reduced to something banal and far from my intentions. Above all the resemblance itself is always questionable, not to mention the variations in colour and liberties taken of dubious taste. I prefer my world to stay in the books or films.

Given all the many forms of expression you have utilised throughout your life, have you ever considered tattooing someone? I would like to know what you really think of tattoo as a form of artistic expression.

I like tattoo, in the sense of a form of expression and an extension of anthropological or cultural manifestations and to this I add scarification, together with other forms of body modification. I admire the work of artists on the body, artists like Orlan, Marina Abramović, or Gina Pane. I am fascinated by the art of Japanese tattoo, the illustrations on skin of sailors in day of yore, the symbology of criminal universes with their codes inked onto skin, the body art of primitive peoples, the excruciating testimony of a rite of passage. I don’t like, or rather I don’t find worthy of attention, decorative tattoo comprised of swirls and ornament and elements without any meaning whatsoever.

Even though I often realise that the value of the imagery is an intimate matter connected to memories or symbols of something extremely personal, which maybe has value only for the wearer of that image. I have never thought about tattooing someone and I wouldn’t want to do it. But at times the idea has crossed my mind of tattooing synthetic skin in order to create pretend anatomical specimens in formaldehyde with subjects I have thought up myself, but executed in the style of the real tattoos worn by criminals or nineteenth century sailors.

What are the projects you are working on at the moment?

Better not to talk about them, I’m superstitious that way. Too often, in the past, I’ve spoken about my plans and they’ve always gone awry. Better to talk about them when they are finished.

What pipe dreams do you have, what objectives in terms of your professional life, that you would love to see come true?

I would love to be able to live off my work, something which today seems an impossible dream.

My final question, and maybe to be honest something I am curious about, which is often asked to directors of horror films, or in any case to those like you who have found a source of creativity in all that is frightening and connected with death. So, is there anything that really disgusts you? Anything that you are afraid of?

There are lots of things that frighten me, I’m a scaredy cat by nature. But what really horrifies me is the pernicious, awful stupidity of human beings.

Thank you so much Stefano for this journey through the dancing shadows that reside in your inner world.

Dancing shadows? A critic of mine once called them existential angst. Maybe they were right. Thank you!

Youtube:stefanobessoni

Instagram:@stefanobessoni

Facebook:Stefano Bessoni