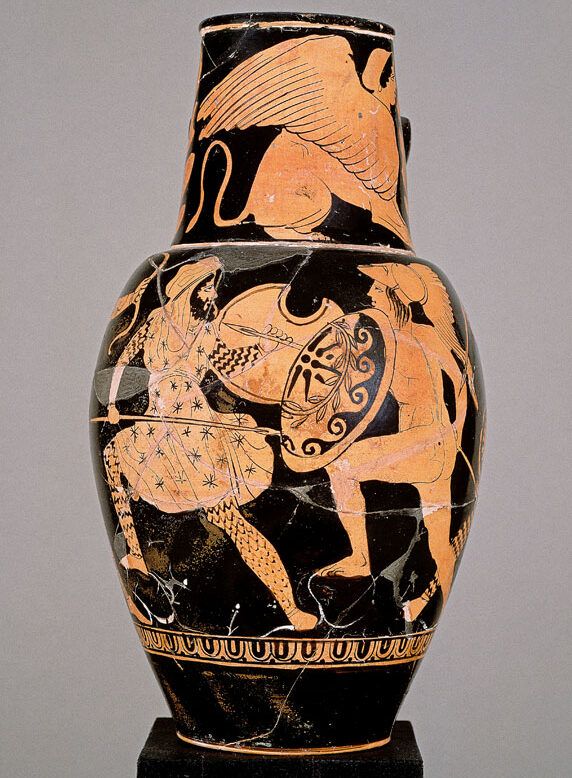

Steganography is the practice of concealing a secret message within another message or a physical object. The word steganography derives from Greek steganographia, which combines the words steganós (στεγανός), meaning “covered or concealed”, and -graphia (γραφή) meaning “writing”.

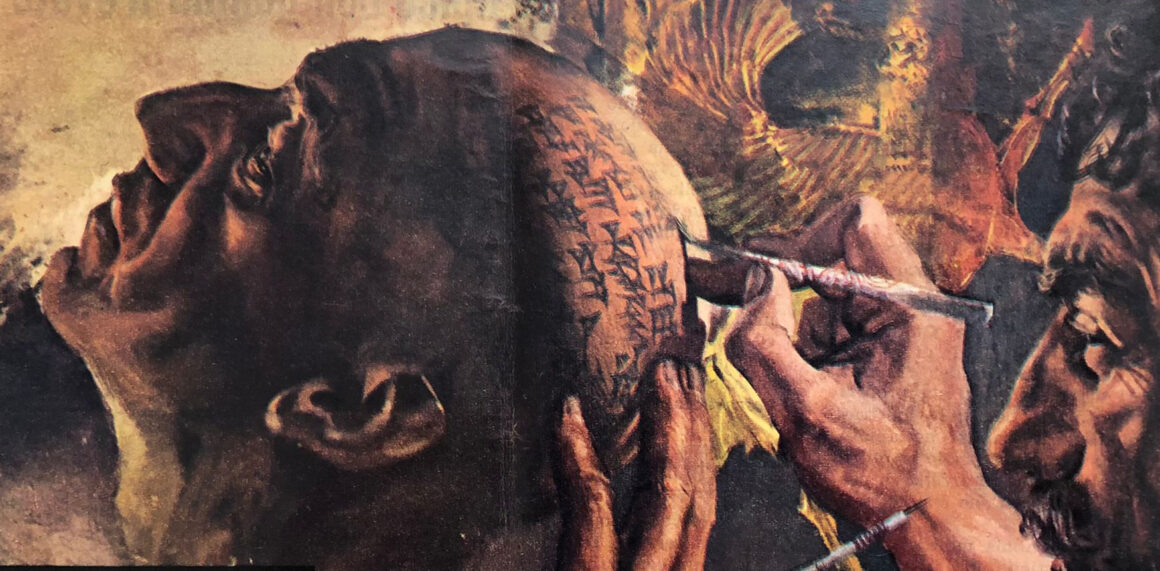

It is interesting to dig into the past and discover that the first example of steganography is closely related to the world of tattooing and to its use for political and uprising purposes.

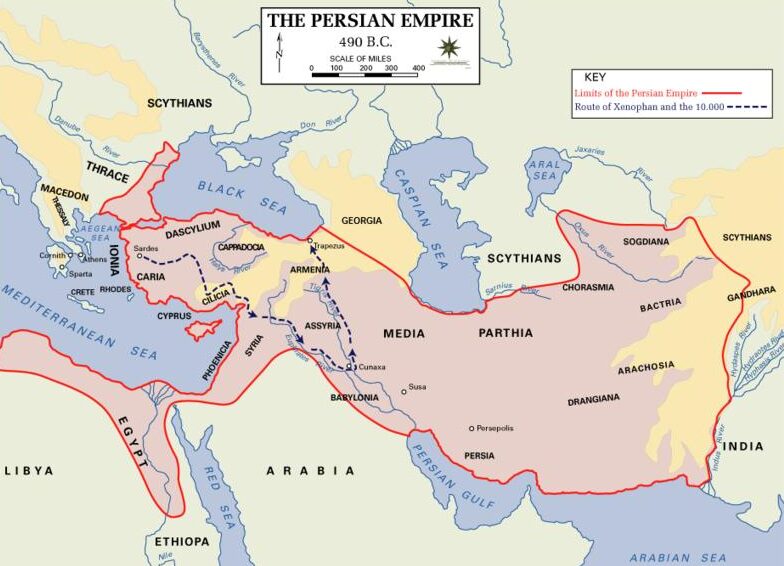

Histiaeus, a Ionian tyrant and ruler of Miletus in the late 6th century BC, led part of the Persian force that engaged Shythians; he had been left in charge of guarding the bridge of triremes, which were left intact as a point of retreat and as a supply line. As a reward, Darius granted Histiaeus a settelment at the mouth of the Strymon River, a strategic location envied by the Persian commander Megabyzus, who suspected the man’s loyalty. Heeding the warning of his trusted commander, Darius relocated Histiaeus who started a revolt in Ionia to regain control of his settlement. (from 499 BC to 493 BC).

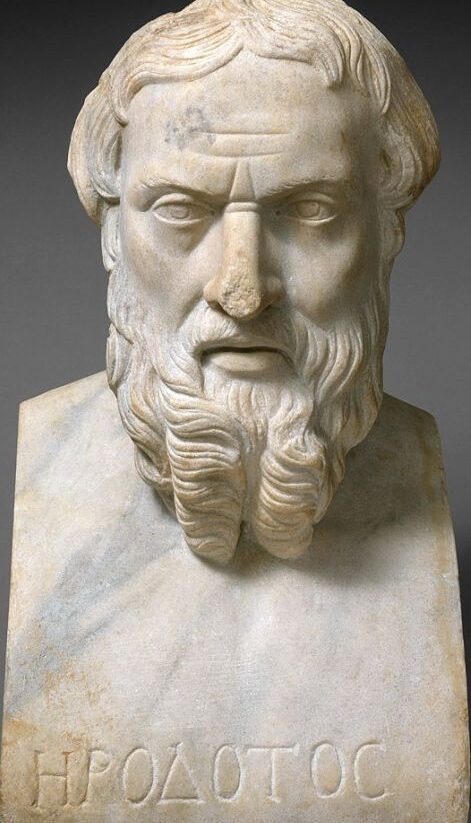

In order to launch the revolt, he had to get a secret message to his ally Aristagoras. His innovative method of conveying the message is well explained by Herodotus in his Historiae, Book V, 440-429 b.C.

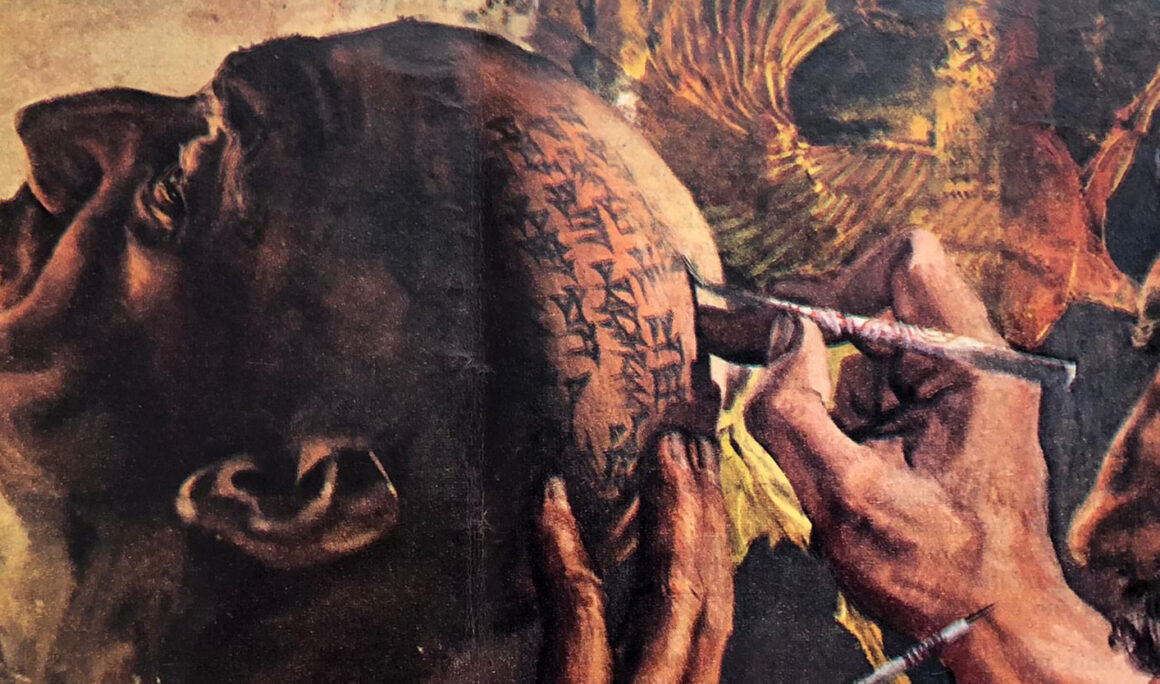

Histiaeus of Miletus first summoned his most trusted slave, whom he insisted was ill. As the preferred treatment, he had the slave’s head shaved. He then ordered the scarification of the slave’s bare head as therapy. The scars were made with a sharp stick, dipped in a colored dye, that is to say, a permanent tattoo. Histiaeus‘ geniality was that while pretending his slave was getting medical treatment, he had the message tattooed on the head of the slave.

He then had the slave’s head wrapped in bandages, so as to obscure the message, and kept him hidden away. After a period of time, the slave’s hair grew back, covering the tattoo. At this point, Histiaeus sent the slave to Aristagoras of Susa, his son-in-law, with the instructions to shave his head when he arrived. This was how the message of urging him to stir the Ionians up against Darius followed by the joining of Histiaeus in the Ionian revolt against the Persian king, unfortunately culminated with the Greek’s defeat.

This ingenious device caught the fancy of later collectors of stratagems; Polyaenus is able to report the message, ‘Histiaeus to Aristagoras: make Ionia revolt’, and Nicephorus Ouranius in the late tenth century says, ‘He pricked letters with pin and ink’.

In conclusion, it should be mentioned that Histiaeus had the slave tattooed in Susa (ancient name of Shush city, Iran). It is then highly likely that the practice of tattooing slaves arrived to the Greeks from the Persians.