A talk with tattoo-researcher Ole Wittmann on Germany’s first professional tattoo artists

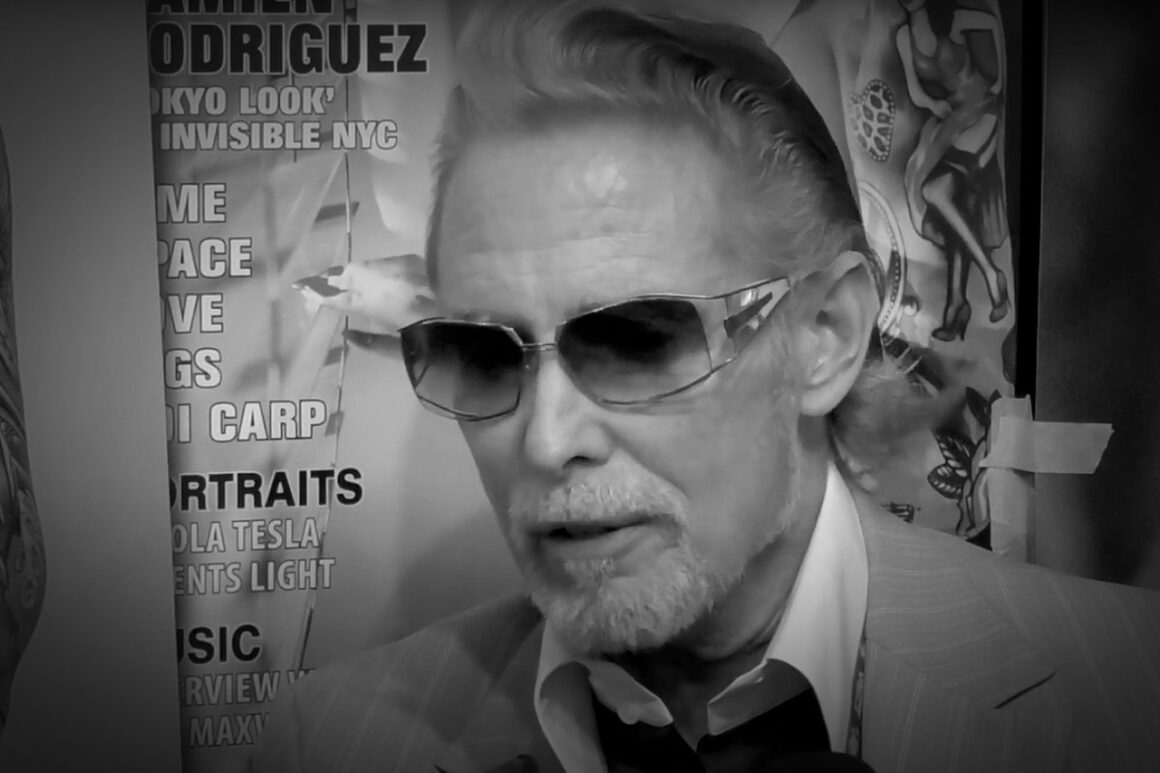

Ole Wittmann is a german art historian with a focus on research on tattoos. In 2015, he wrote his doctoral thesis on the human body as an image carrier for tattoos. His dissertation »Tattoos in der Kunst« (tattooing in the fine arts) was published in 2017.

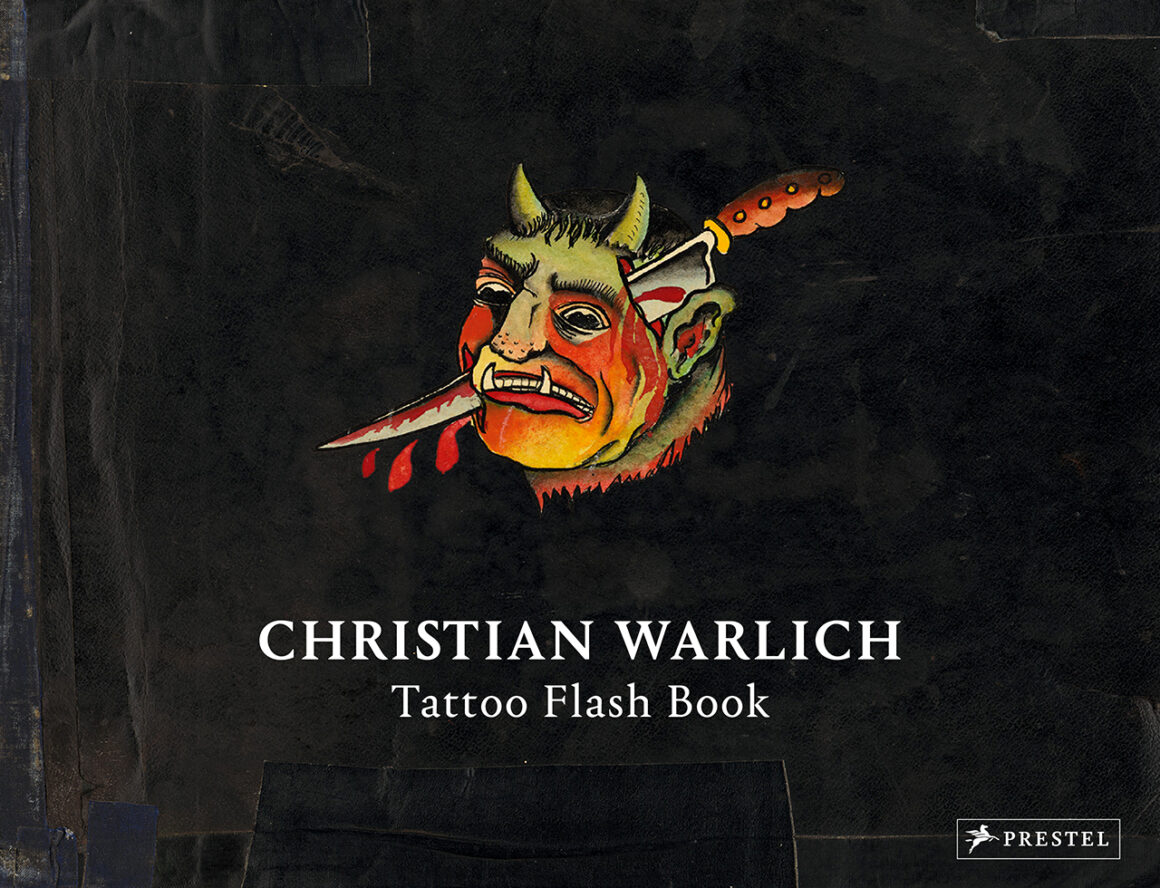

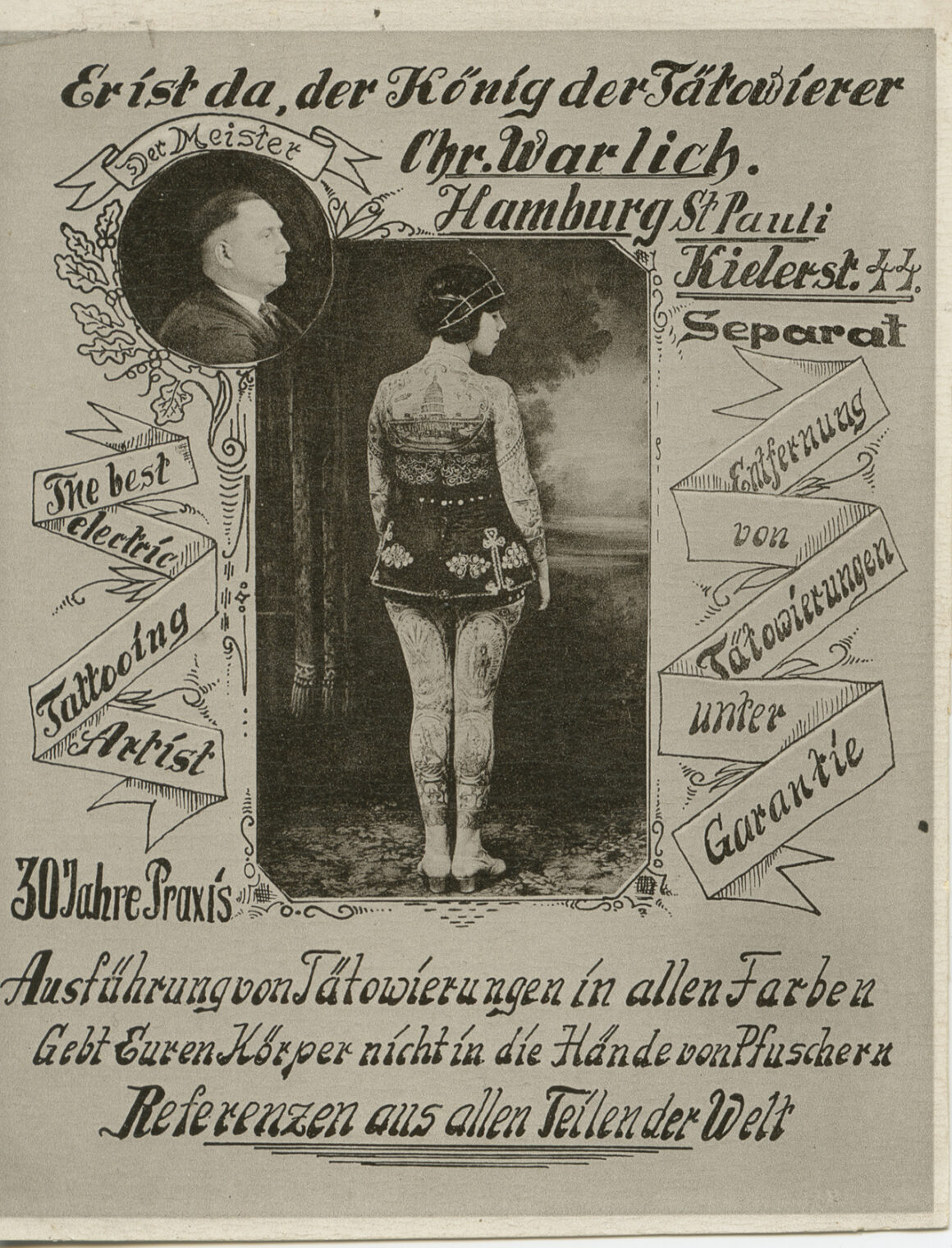

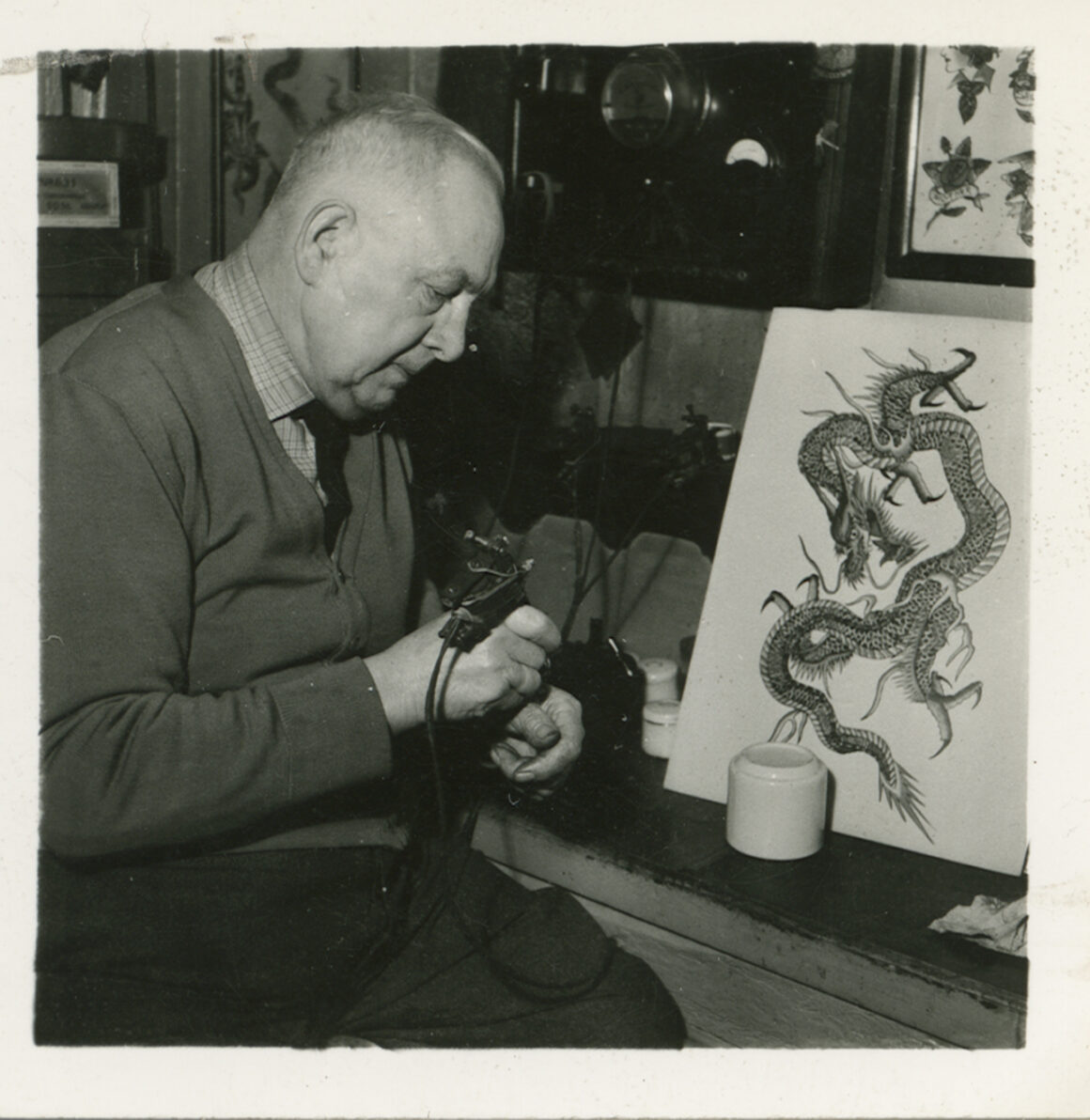

As a postdoctoral fellow he led the research project »The Estate of the Hamburg Tattooist Christian Warlich (1891-1964)«. In 2019/20, he curated the special exhibition »Tattoo Legends. Christian Warlich on St. Pauli« at the Museum of Hamburg History.

He is also a founding member, research director and board member of the Institute for German Tattoo History e.V. (IDTG) and managing director of Nachlass Warlich, which distributes the product Warlich Rum.

We had a talk with Ole to shed some light on these very early years of tattooing in Germany.

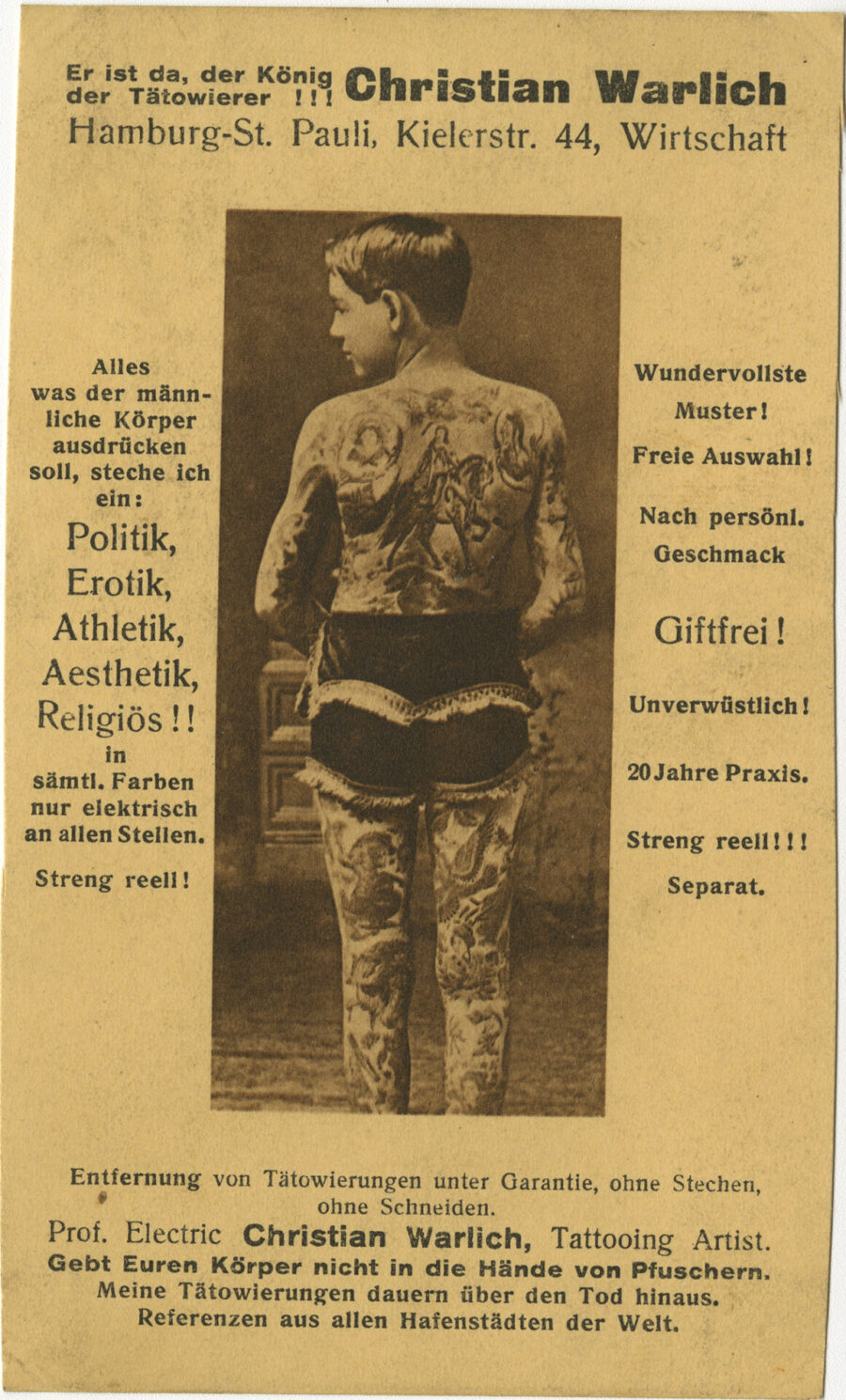

Ole, you research German tattoo history and especially life and work of the famous German tattoo artist Christian Warlich (1891 – 1964) in Hamburg. If I remember it correctly, he called himself, the king of tattooists. Was Warlich the first professional german tattooist?

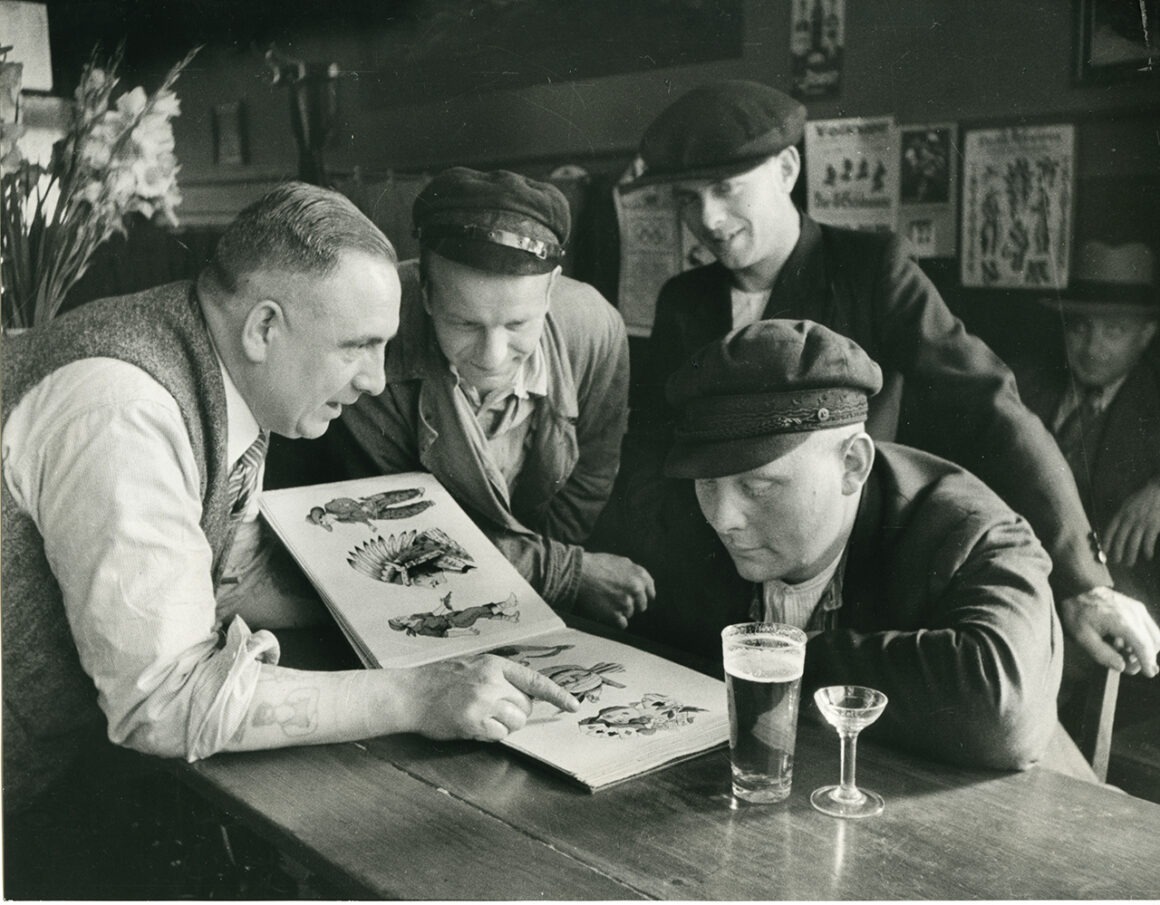

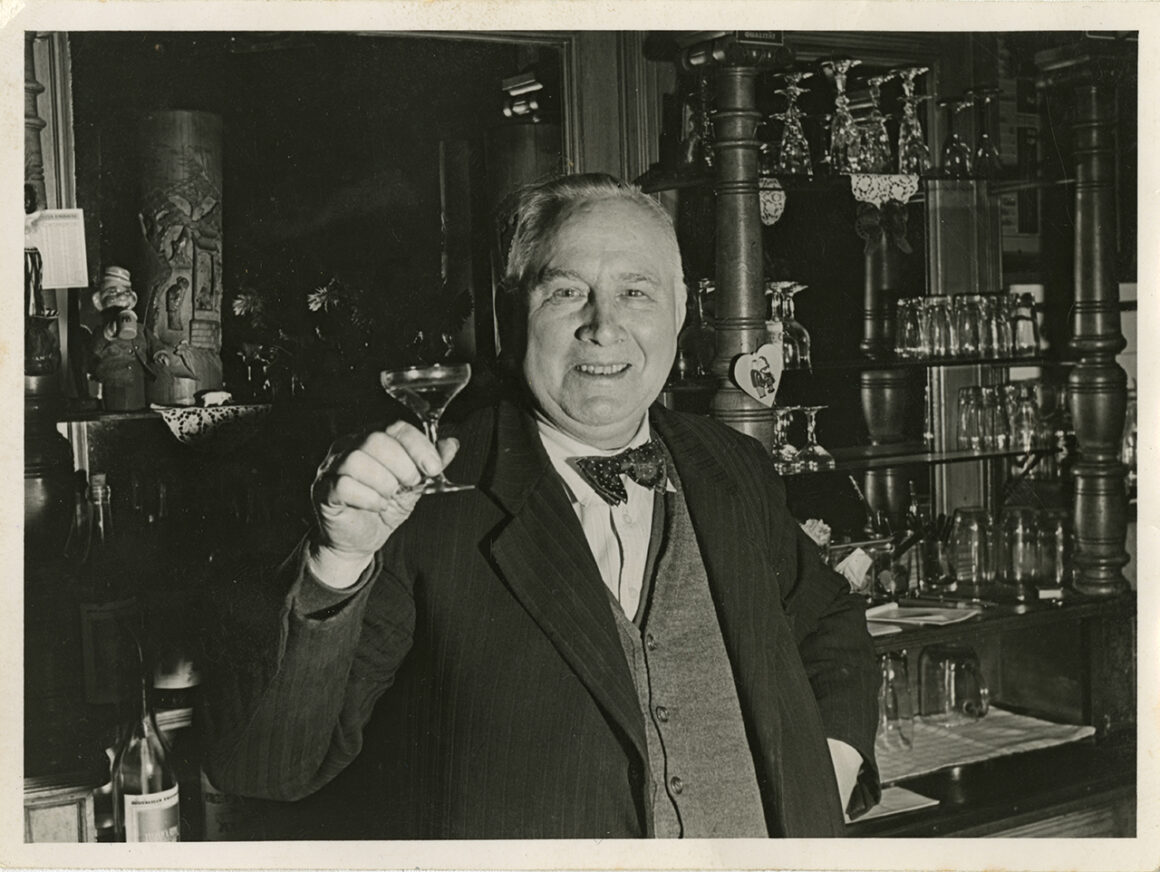

No, tattoo artists who earned their living by tattooing existed even before Warlich. In Hamburg, for example, there was Karl Finke. However, Warlich has strongly professionalized the trade. He had an area for tattooing in his grog pub and thus a kind of publicly accessible tattoo studio.

What made Warlich stand out from other tattooists? Was he better than the others or was he just better at promoting himself?

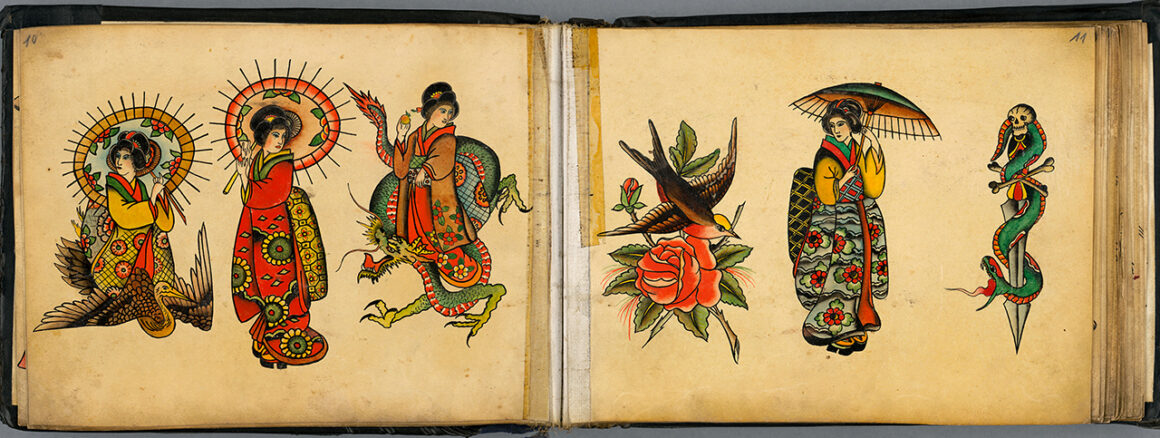

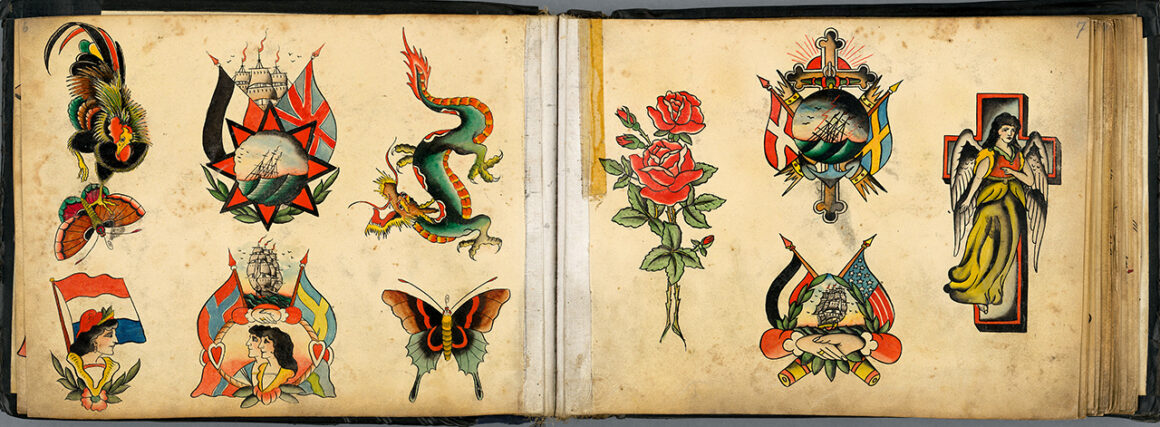

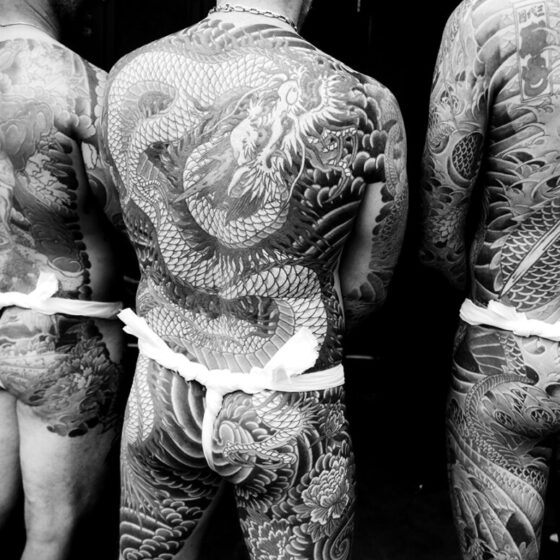

Before Warlich, tattooing was a mobile profession. Tattoo artists had everything they needed to work with them and tattooed where they found customers: in pubs, on boats, in parks, at fairs, etc. He changed the tattoo trade in that he took it to a new level. He not only worked at a fixed address, but stood out in terms of quality of his work. He also knew how to promote himself and his work appropriately.

The image we have of tattooists in the first half of the twentieth century – or earlier – is that of a guy who lures drunken sailors and easy women into a shady workshop to rip them off. Is that completely wrong or can you paint a more accurate picture of tattooists around 1900?

Little is known about Hamburg tattoo artists at the turn of the century. In fact, there are indications that some tattoo artists had a rather unsteady lifestyle and pursued various activities. Also the one or other connection to a crime is handed down.

What made people like Warlich become tattooists? It was far from being seen as a normal profession as we see it today?

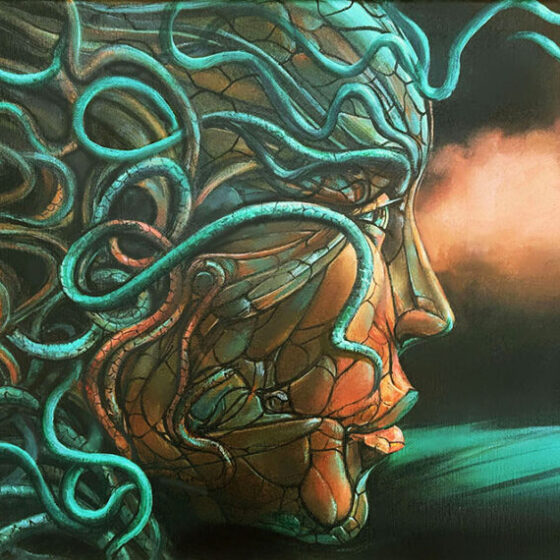

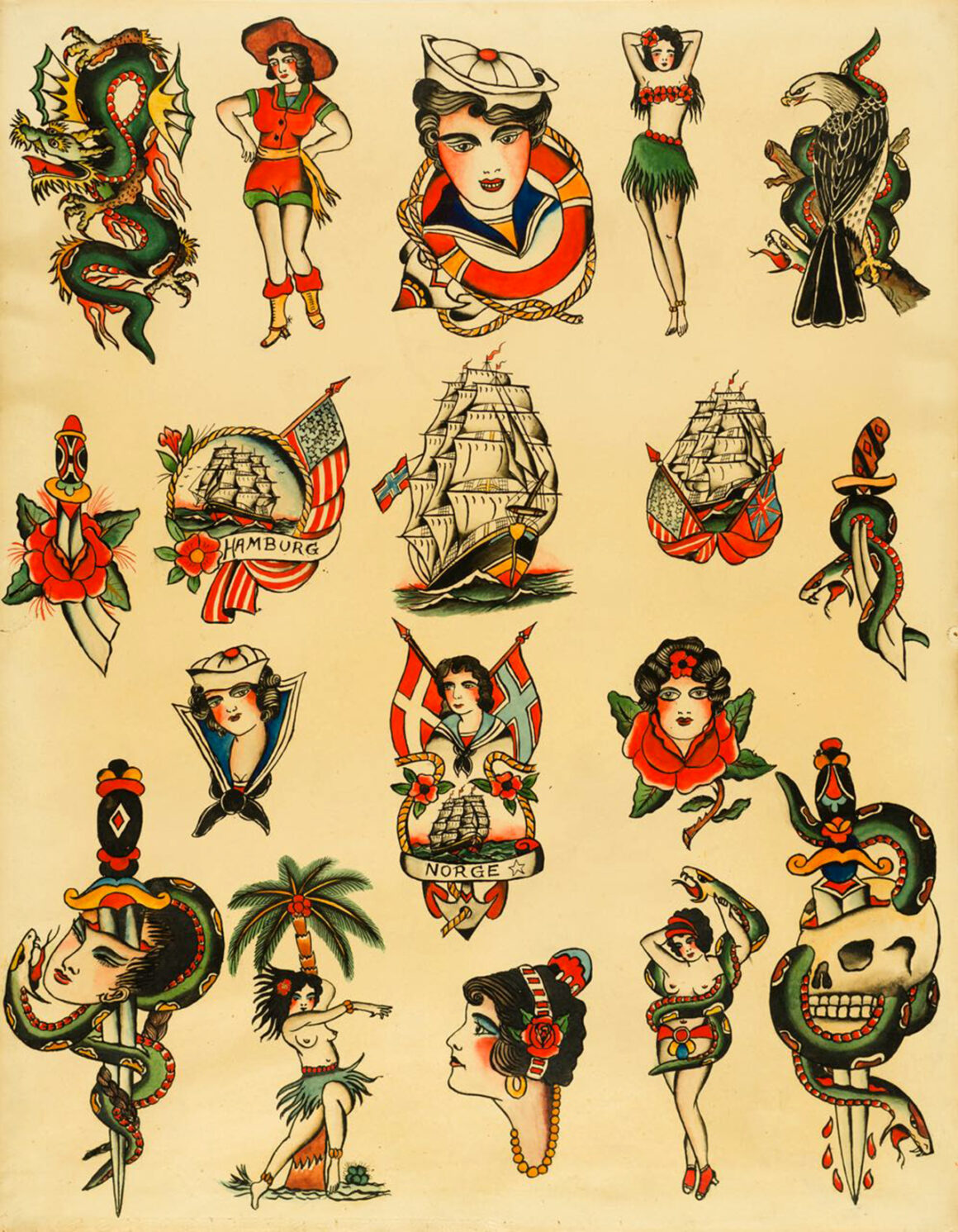

Why Warlich became a tattoo artist is not known. But he seems to have been driven by a great passion since, according to his own statement, he tattooed schoolmates as a child. The high standard of his work and his concern to translate works of fine art into tattoos also indicate this.

Certainly, the profession of tattoo artist was then much more unusual than today.

This becomes clear when you consider that around 1930 there were about a dozen more or less professional tattoo artists in Germany.

On the one hand we think of sailors or prostitutes as clients of tattooists at that time, but it’s also known that a lot of the European high nobility found it chic to get tattoos – how could they go together?

I don’t think that’s a contradiction. Getting a tattoo can be a kind of basic need and is, in a way, an anthropological constant. It doesn’t matter which class you belong to. That may influence showing tattoos, but not the desire to have them.

What are your main sources to research German tattoo history? I could imagine that the tattoo culture wasn’t seen as worth preserving at that time by museums or other cultural institutions, which makes it probably harder?

Yes that’s right, few institutions were aware of the importance of tattoo-specific objects. Hardly any museum has collected them. Exceptions are, for example, the Museum of Hamburg History, the Dresden State Art Collections, the Institute for Saxon History and Folklore or the Cantonal Library of Appenzell Ausserrhoden. An important source in literature is the text »Die Tätowierung in den deutschen Hafenstädten« (The tattoo in german harbor cities) written by Adolf Spamer in 1933.

Samuel O’Reilly invented an electric tattoo machine in 1891, so did all tattooists use electric tools after that?

This cannot be said for Germany, as there is no documentation on this. In any case, Warlich and Finke worked with tattoo machines.

If my memory serves me right, I once saw a sign by Warlich, claiming to use »poison-free« colors – do you know what they were actually made of?

No, that is not known.

Warlich also used a famous and mysterious tincture that enabled him to remove tattoos – they detached in one piece from the clients skin and he collected them in a box. Did someone ever find out what he used?

Yes, I was actually able to find that out as part of my research project on Christian Warlich. There was an incident that led to Warlich having to submit his recipe to the health authorities. The document listed all the ingredients. A pharmacist remixed it and was able to verify that it worked.

Today it is normal for artists all over the world to exchange ideas, inspiration – how was that in the “old times”? Was there more competition or did the artists of those days also have contact among each other to keep each other updated on technologies or designs?

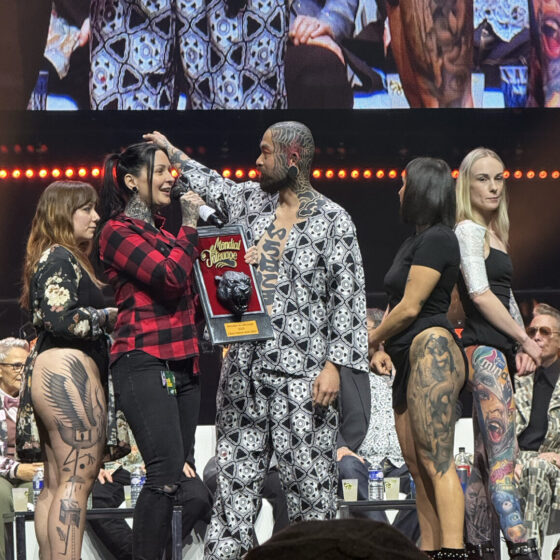

Also at that time tattoo artists have exchanged ideas and information. Initially through personal contact or by mail. Warlich was, for example, in exchange with Tattoo Ole in Copenhagen and much speaks for the fact that he also had contact with Charlie Wagner in New York City. In the seventies, the first tattoo meetings took place in Germany and organizations were formed.

Tattoo artist Herbert Hoffmann, who died in 2010, often claimed that during the Nazi-era tattooing was completely forbidden in Germany and tattooists were likely to be prosecuted. Is that correct? How did tattooists in Germany adapt in that time?

Hoffmann was the most famous Hamburg tattoo artist after Warlich. The Nazi period is an interesting chapter in German tattoo history. Here, too, there are many myths. One is that tattooing was forbidden during the time. I tried to verify this as part of my dissertation. In fact, there is no decree or law that says that tattooing was forbidden.

Of course, this does not mean that tattoo artists were not persecuted.

After all, arbitrariness prevailed and even a politically undesirable tattoo motif or a lifestyle that was not in conformity with the political system could lead to arrest. Also, I once read that the tattoo artist Wilhelm Blumberg had been imprisoned because he was a tattoo artist. But it is also possible that he was Jewish and therefore imprisoned. You really have to do a very thorough fact check when writing tattoo history.

As far as I know, a lot of things from Christian Warlich were passed on to his client Tattoo Theo / Theodor Vetter, a tattoo enthusiast who died in 2004, but was more or less lost after Theos death. Have you been able to find some of Warlich’s legacy?

Yes, the research project on Warlich has succeeded in locating most of the objects. Fortunately, part of Warlich’s estate has been in the care of the Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte since 1965. The part that belonged to Vetter is now in the possession of the collector William Robinson, who today runs the Tattoo Museum Varkhaus in Finland. Other parts are owned by the Vetter family and in the collection of Jimmie Skuse.

Where can people learn more about German tattoo history now?

The publication by Adolf Spamer mentioned above is still a rich source. My books on tattoos in art, Christian Warlich and Karl Finke also give an insight into German tattoo history. The latter two have been published in a bilingual edition (German/English). The most important place to go in the future is probably the Institut für deutsche Tattoo-Geschichte/Institute for German Tattoo History (IDTG), which is expected to publish its first book in 2023/24.