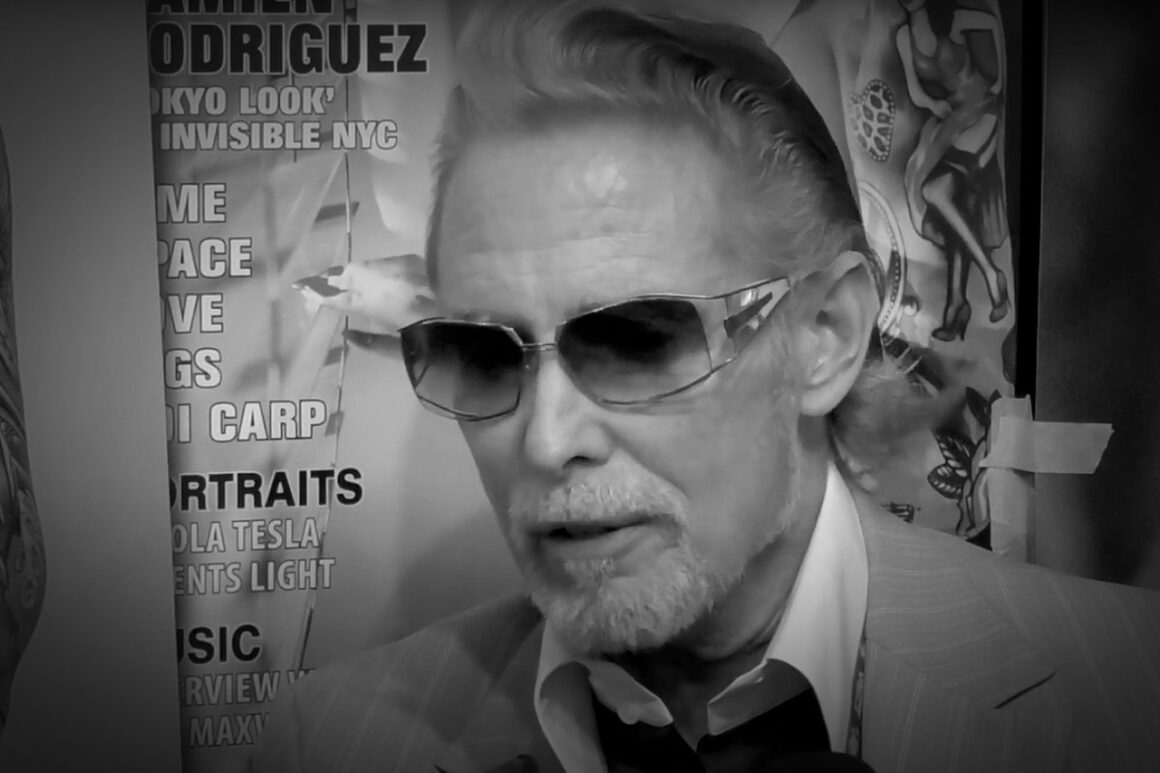

Lars Krutak is a Research Associate at the Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and a worldwide renowned expert for the history of traditional tattooing all around the globe.

His work helps to preserve and to better understand the tattoo culture of indigenous people from the Philippines to Canada, from India to South America and from Borneo to Siberia.

Clicking on the link above shows you a selection of just some of his publications; Lars Krutak is in the top 1% of all researchers on academia.edu.

However, Lars is not the kind of scientist who just works for creating heaps of scientific literature to which only few educated have access; he is the kind of guy who wants to share and explain the results of his researches to a wide audience. So we were happy that in between his travels, lectures and book projects he found some time to speak about his work and his conclusions.

See Lars’ recent project in the field with the Naga of India. More information about the project can be seen in the YouTube description.

Charles Darwin and also James Cook came on their travels to the conclusion that there is no culture or tribe in the world that doesn’t practice tattooing or at least hasn’t practiced it over the course of it’s history; can you confirm their observation?

LARS: In the “Descent of Man,” Darwin did offer a quote that tattooing was a universal human practice and Cook noted something similar in his writings. While various forms of permanent and impermanent body-modification practice have been part of human history since the beginning of recorded time, there are countless societies and Indigenous cultures where tattooing was not practiced.

For quite a while the ice-mummy Ötzi, discovered in the Italian alps and estimated to be around 5200 years old, was said to be the oldest proof of tattooing, but in the meantime tattooed mummys were also found in South America, Egypt, Siberia… so which one is the oldest tattooed human body discovered so far?

LARS: At present, Ötzi holds the record for the oldest tattoos (geometric) found on a human body. At the British Museum two Predynastic Egyptian mummies (a male and female) from the Gebelein site possess the world’s oldest figurative tattoos (animals and a staff), and they are almost as old as Ötzi (~5000-5100 years old). However, soon you will be reading about tattoos in the global media that are the oldest in the world, but I cannot provide any other details – it’s a secret!

What is it that makes tattooing so universal? Where does the urge to tattoo oneself come from? Can you see differences in the meaning of tattoos in traditional societies compared to our modern-day tattoo-scene (apart from the designs and patterns)?

LARS: Tattooed skin embodies a powerful narrative function and has always been fundamental in establishing personal and collective identity. For example, Indigenous tattoos represented the individual like a name and transmitted aspects of a person’s biography (rites of passage, other achievements, etc.) through their lifetimes and onwards into the afterlife.

Tattoos transmitted information regarding where a person came from, what territory they belonged to, and who their ancestors were.

Humans have produced tattoos for millennia because there is something that demands to be said that cannot otherwise be expressed via other mediums of communication, like writing or language.

No matter where we come from, we have this natural impulse to mark significant life changing events on our bodies, and tattooing is a kind of social media of memories, thoughts, and feelings that enable us to not only interact with one another and manage the cultural demands we live in, but to make our own personal histories visible.

Quite often the tattoos of tribes living in traditional communities are frowned upon by the western-oriented society of their respective countries who see them as a sign of backwardness. How do such tribal communities react when you show them your interest in their culture?

LARS: I should add that sometimes even young people in tribal communities look down on the tattoos of their elders because they are seen as backward and not modern. For example, I have interviewed many tribal youth and they are more interested in Western tattoos because they are more colorful as compared to the traditional blackwork of their ancestral traditions. Also, today numerous entertainers, sports stars, and other famous people are tattooed in various styles which adds to the perceived status of these kinds of tattoos in contrast to tribal tattoos.

I spend most of my time in the field working with tattooed elders and peoples’ grandparents because they often represent the last generation of tattoo bearers.

Since I have tattoos, that helps break the ice because even though I come from a different culture, tattooed elders immediately understand (and see) that we have something in common. I also arrive with lots of tattoo knowledge based on homework, Indigenous tattoo terms, and old pictures, not to mention gifts like old reading glasses, nail clippers, beads, and other useful things.

All of these things help break down cultural barriers and establish my respect for local culture. People can tell that I am not a tourist (!) and that I am very serious researcher who wants to learn more about the history and stories behind their tattoos. Working with elders is a benefit in itself, because in Indigenous communities, elders are highly respected for their traditional knowledge and leadership. So my work usually generates a lot of positive community interest.

What are the purposes of tattooing in indigenous cultures?

LARS: Throughout history, Indigenous people have applied tattoos to living skin in their attempts to beautify, heal, empower, or carry the body into the afterlife. Others were marked for their achievements in warfare, weaving, or hunting. Some tattoos were believed to repel evil spirits whereas others might draw upon ancestral power for the benefit of the wearer.

Is tattooing in tribal cultures linked to other arts and handcrafts and arts of these cultures?

LARS: In many Indigenous cultures the same patterns used in tattooing might also be used in basketry, weaving, amulets, or carving traditions. Among the Iban of Borneo, women who excelled in weaving ikat fabrics called pua kumbu’ were allowed to bear specific tattoo patterns depending on what stage of mastery she had acquired in weaving. The highest stage of weaver, or those women who created their own patterns with the assistance of spirit helpers, wove ceremonial fabrics used to received enemy heads taken in combat by men; this was called kayau indu’ or “women’s war.” For this feat, weavers of this class could earn the right to hand tattoos (tegulun) which were also worn by veteran warriors who had taken human heads.

Today we think of tattooing as putting color in the skin with a needle, by hand or machine – but have there also been other tools and techniques over the times and different cultures?

LARS: Worldwide various substances have been used to create tattooing ink. Among Indigenous peoples, vegetable carbon (e.g., soot) was the most common. As far as traditional techniques, skin-stitching or needle-and-thread tattooing where the pigmented thread is drawn through the skin with a needle, was used across the Arctic and Native North America. Hand-poking, where the design is poked into the skin with a sharp pigment-tipped needle, was a more common method of tattoo application.

Simple needles, usually two in number obtained from cactus or palm-tree spines, were wound together with cotton thread to prick the skin. The small space between the needle tips acted as a reservoir that held the liquid tattoo pigment in place. However, the needles had to be dabbed into the pigment after a few pricks had been made to keep this reservoir full. This technique was employed in the Middle East, Balkans, Amazon and other regions of South America, Northwest Mexico and the American Southwest.

Hand-poked tattoos continue to be given across Indochina and Japan. Hand-tapping, where one or more comb-like rows of needles is attached at a right angle to the end of a baton and struck with a heavy object or mallet, is perhaps the most ubiquitous traditional technique and Indigenous to Oceania, Southeast Asia and parts of Melanesia (e.g., Papua New Guinea). In some regions of Africa, North America and Asia, the method of scar tattooing was employed.

Here, skin incisions were made with a lancet (obsidian, iron, etc.), and the tattooing pigment was immediately rubbed into the open wounds.

There is a very rare technique that I call “hand-hammering” that might be ancestral to hand-tapping. It is found only in a small region of Northeast India among the Konyak and Wancho Naga. Female technicians fashioned an adze-like tool with a row of bush thorns and basically hammered the needles into the skin.

In the past few years, tribal tattoo patterns from some indigenous tribes of Borneo or from the native New Zealanders, the Maori, have become very popular in the west, but some of the traditional cultures see this as a form of cultural appropriation; how do you think about this?

LARS: Tattooing is more popular today than perhaps at any point in its history and as a tradition and practice it has always been evolving over the millennia. For example, I know several Indigenous cultures who borrowed and copied the patterns of other societies to make them their own. And today, many Indigenous tattoo artists fuse and mix Western designs with tribal patterns to create hybrid and contemporary styles for their Indigenous and non-Indigenous clients. That being said, I think it is very important to work with a respected tattoo artist who knows the cultural protocols involved in giving and receiving a tribally-inspired tattoo, and what would be appropriate for their client to wear.

Is there an especially remarkable encounter or anecdote that you can tell from your research in that field?

When I started my tattoo studies, there was a widely held myth across Indigenous cultures that the profession of tattoo artist was male-centered. But this was simply not true, and as I began compiling research and conducting fieldwork it was apparent that women performed this role more often than not. With this in mind I wanted to set the record straight, so in 2007 I wrote my first book The Tattooing Arts of the Tribal Women.

Globally, there still are many Indigenous groups whose tattooing traditions are not well-known, especially in places like Amazonia and northern Myanmar, and research should be conducted to preserve this vanishing cultural and artistic heritage. Topically, however, perhaps the least studied aspect of Indigenous tattooing is its use as a medicinal therapy (e.g., rheumatism, joint pain, etc.) and its role in boosting the immune system. More specifically, little research has been conducted regarding the pigments used by ancient and more recent peoples. I have documented numerous Indigenous plants used in the preparation of tattooing ink as well as in aftercare products, but most of these species are only known locally and do not have English language equivalents. Thus, these plants have not been identified scientifically and they may yield important discoveries.

Can you tell us about future projects you might be working on?

LARS: In September, the new Humboldt Forum Museum in Berlin will showcase several of my photos on the tattooing traditions of the Naga people of India and Myanmar. A series of special lectures and events will occur at the same time because the museum is opening a new Asian exhibition space where these photos can be seen. 2023 looks to be a big year for me. I have two new books coming out, a huge project 20 years in the making covering the Indigenous tattoos of Asia and another book with a Japanese publisher entitled The World Atlas of Tribal Tattooing. Updates on these and other projects will be posted on my website www.larskrutak.com. Also, I have two chapters in the 2023 Oxford Handbook on the Archaeology and Anthropology of Body Modification: one focuses on prehistoric “tattooed” human figurines in Japan, Arctic, Egypt, and South America and the other is on the anthropology of Indigenous tattooing that is co-written with Indigenous tattoo artist Dion Kaszas of Canada.