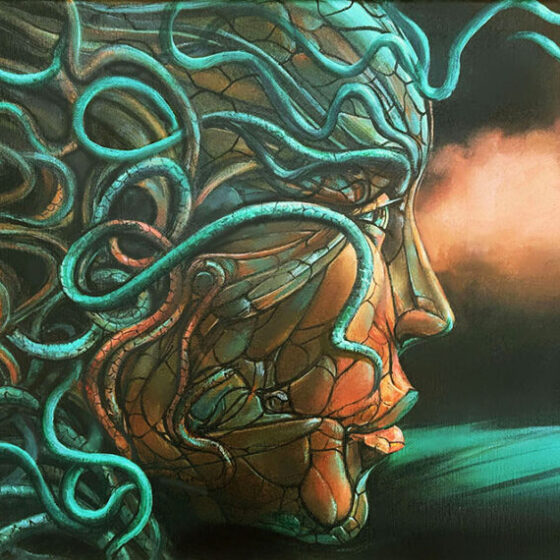

A new exhibition at textile-specialist Gallery76 in NSW, Australia, explores the parallels between tattooing and embroidery. ‘Not That Kind Of Needle’ was inspired by a growing trend in tattooing where artists create realistic tattoos that look as though they were stitched into the skin.

Curator April Spiers sought a selection of talented tattooers from around the globe who specialise in the style to take part in the display, often weaving stories of their cultural heritage through their tattooing.

How did you come across the phenomenon of ‘embroidered tattoos’?

Where else – the wonderful world of Instagram! As an embroidery and textile gallery we follow a lot of #embroidery hashtags as a way to discover upcoming embroidery artists and honestly, we went down a black hole into the world of embroidered tattoos; it was fantastic! What was incredible was not just that these artists were using embroidery designs but that they were painstakingly recreating the appearance of three-dimensional thread in tattoo ink.

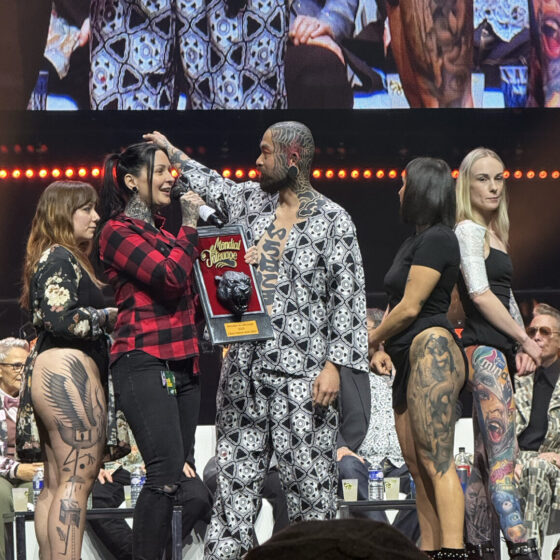

It’s been a growing niche in tattooing but there are still few who specialise in this style. Which artists did you choose to feature and why?

In Not That Kind of Needle, we really wanted to give our visitors a glimpse into the international nature of this trend so we tried to feature artists from different parts of the world. As a gallery who specialises in embroidery art we wanted to show a variety of styles – from machine embroidered patches to more traditional folk embroidery and cross-stitch. Mexico is very much the beating heart of this trend and many international artists who now work with embroidered tattoos first learnt of it in Mexico. We have a number of fantastic Mexican artists in the exhibition including Alicia Casale, Alberto Rojo, Tata MucinÞo, and Maria Brunereau.

Like tattooing, embroidery is a craft that has spanned millennia. Almost every world culture has an embroidery tradition of some kind. It’s a medium that is diverse and yet unifying and we wanted to capture that in this exhibition.

One of the things I love about the artists working with embroidered tattoos is their genuine love of traditional embroidery. Many of them were inspired to begin including it in their art practice by fond memories of their mother or grandmother stitching, and there is something so beautiful about this intergenerational acknowledgement of craft.

Embroidery has also been traditionally seen (in many cultures) as a feminine craft and most of the practicing tattoo artists in our exhibition are women. Many of their clients are choosing to be tattooed in this way because of the direct link it has to women’s history and women’s craft. Again, while embroidery as an art form has a long history of protest, it is often also perceived as being very “safe” and “domestic” and there is something about pairing this tradition with the more “risqué” practice of tattooing that feels delightfully poignant and frankly, incredibly satisfying!

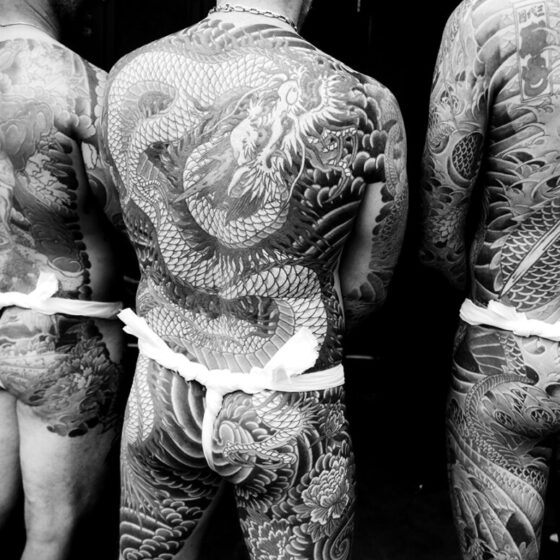

Both tattooing and embroidery have historically been used as tools for storytelling (I’m thinking of Berber patterns weaved into rugs and on skin, the meanings of each symbol passed down for generations). What parallels have you discovered between the two crafts?

Absolutely! I think partly because both tattooing and embroidery are worn on the body, stories and symbols of significance were important to include, both to embrace your own identity and as a way to communicate it to others. There is also a great parallel of including deliberately hidden meanings in both crafts – insider jokes or hidden code. There are fantastic stories of female spies in WWII using knitting or silk knotting to record and pass on important information about the Nazi war machine – who would suspect the elderly woman sitting at the railway station calmly knitting away? I also love the story of the WWII British POW who embroidered an apparently “traditional” embroidery sampler with threads unravelled from a pullover “borrowed” from a Greek general. Hidden into the outer border in embroidered morse code, the sampler reads “God Save the King” and, on the inner border the hidden code reads “F**k Hitler”.

Similarly, many cultural traditions include symbols in their embroidery patterns, either of identification or symbols to bring good fortune to the wearer or protect the wearer from evil. You often see these propitious symbols or characters embroidered on clothing, especially children’s clothing. We have a beautiful set of 1890s embroidered children’s earmuffs from Japan which are decorated with embroidered reeds (reeds are a homophone for “passing exams”) held in our historic collection.

Ukranian embroidery is another tradition that is heavily pregnant with symbolism – crosses protect from evil, different animals and birds have different meanings and so on. While the coding and symbolism might differ between embroidery and tattoos, there is no doubt that both are often imbued with meaning and, sometimes, power, which we want to harness or project in some way.

Which are your favourite pieces from the exhibition? Can you tell us about any of the works in more detail?

We definitely can’t choose a favourite! I love the practice of Andrea Kopecka (a Slovakian tattoo artist). She researches traditional Slovakian embroidery designs from both published patterns and archival material, as well as consulting with ethnologists and second-hand traditional costume sellers from across Slovakia. Kopecka also involves her clients in her process, asking them to look for fragments of traditional costumes and embroideries in their homes. By incorporating these very traditional Slovak folk embroidery patterns, she hopes to make a visual connection to the cultural heritage and challenge the conservative prejudices of the older generations who mostly associate tattooing with the prison tattoos of the communist regime.

Another fantastic artist in the exhibition is Kyeongjin Lee from South Korea. Lee’s work is inspired by the embroideries worked on Hanbok (traditional Korean dress). Like all the artists featured in Not That Kind of Needle – Lee does an incredible job of translating the individual stitches into ink.

Lastly, can you tell us about your gallery space? Is it possible to view the works online?

The exhibition originally opened just as Sydney went into a four-month lockdown so we put together a short 8min film of the show which is up on our YouTube channel. Normally, we are open 7 days a week and you can visit us at 76 Queen Street in Sydney’s inner west.

We also had a fascinating conversation with tattoo historian Dr. Matt Lodder about the many crossovers between embroidery and tattooing as practices. His main argument is that tattoos, like embroidery, are the products of their cultural context and reflect the aesthetic and social trends of their day.

We are so loving following this trend of embroidered tattoos at Gallery76 and can’t wait to see how it evolves over the next few years!