Tattoos of Chinese characters have long been popular outside of China. There are many stories about these tattoos not meaning what people think they mean.

For example, at an English wedding, I once noticed a guest who had a large tattoo of the Chinese character for ‘dog’ on her calf. But most people largely like these characters because of how they look rather than what they mean. This is arguably the case in China itself, too.

With this in mind, let’s take a look at the four areas of Chinese characters you should consider before getting one of these tattooed.

1. Type of character

Today, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other overseas of the Chinese communities use the traditional Chinese characters. But Mainland China, where most Chinese speakers live (1.6 billion of them), have used simplified Chinese characters since the 1970s.

Only about 30% of the characters in each script are different. But these are more or less the 30% most commonly used ones. So, the difference between each type is clear:

Simplified: 学而时习之,不亦说乎?有朋自远方来,不亦乐乎?

Traditional: 學而時習之,不亦說乎?有朋自遠方來,不亦樂乎?

Traditional characters are more complex. Sometimes this is immediately clear, for example: 学 vs 學. Other times, it’s more subtle: 来 vs 來.

Even in Mainland China, traditional Chinese characters are still favoured for ceremonial or decorative use. They are generally seen as more beautiful and imbued with heritage and meaning.

2. Format

Chinese characters used to be written across scrolls vertically and from the right to the left without punctuation. Today, Mainland China uses the Western format of writing horizontally and from left to right with punctuation.

In many books and newspapers where traditional Chinese characters are still used, they are still printed in the old way (but with punctuation). However, even in these medium, computers, phones, subtitles, etc., writing in the Western format becomes more practical.

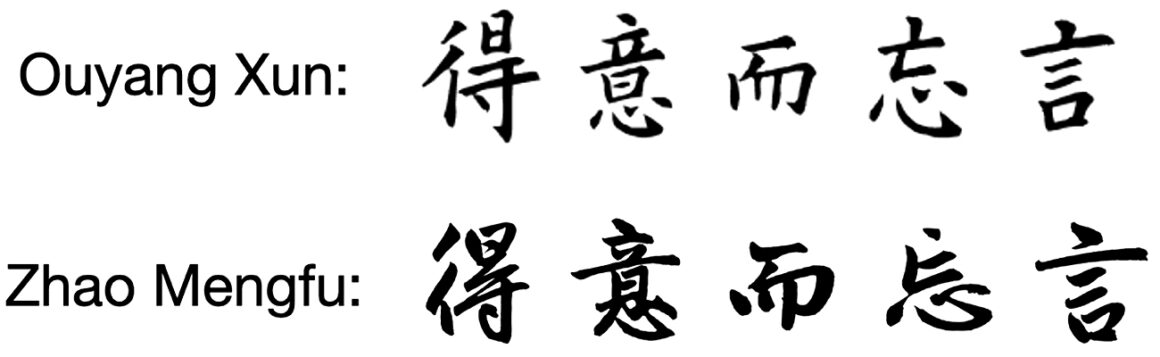

Here is the same text (a famous poem by Li Bai (701 – 762 AD)) written in each way:

As with traditional characters, the old-style format is still favoured for commemorative or special occasions.

3. Script

Like English, Chinese has different fonts. In its calligraphy (which some of its fonts imitate), it has several different scripts.

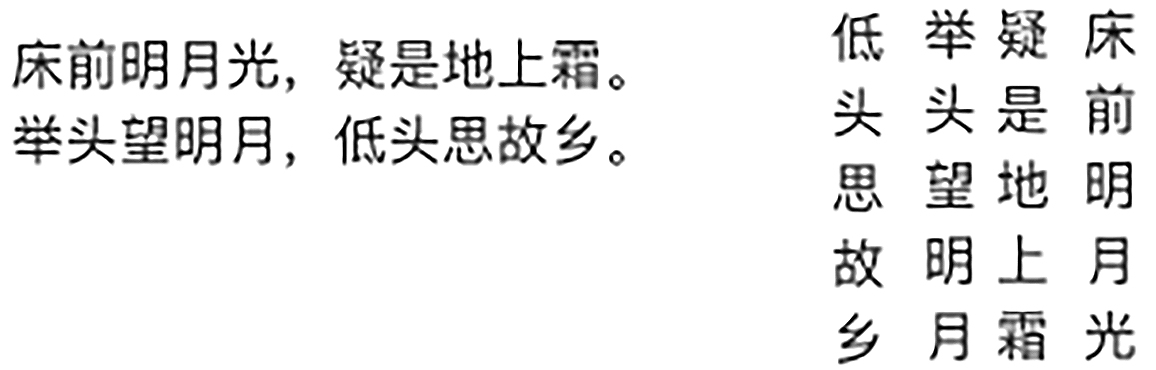

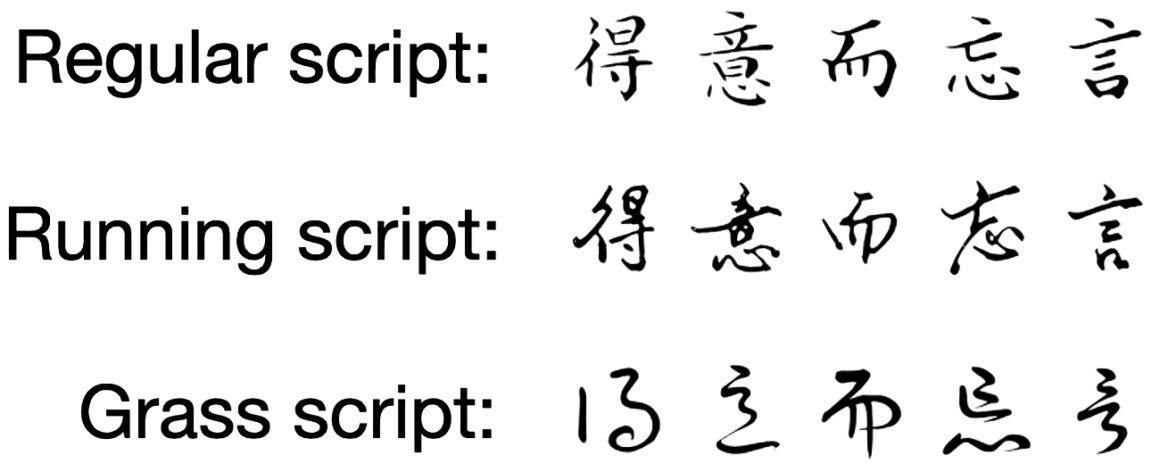

There are three main scripts. Regular script is essentially the standard, official style. Running script (also known as semi-cursive script) is essentially a more flamboyant version of regular script. And grass script (or cursive script) is an extremely ‘fast’ and – to all but a few experts – illegible script.

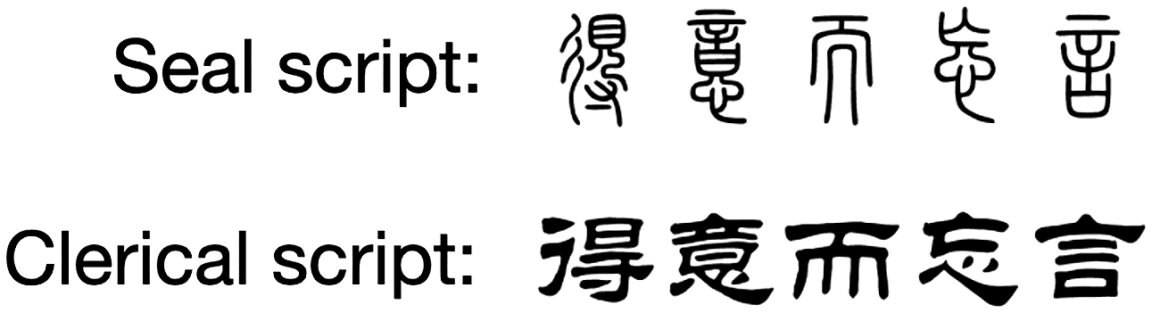

There are even older styles, too:

Chinese calligraphy has thousands of years’ worth of master calligraphers, each with their own unique taken on any given script.

Below, for example, are two samples of regular script. The first is in the style of the influential Tang dynasty official and calligrapher, Ouyang Xun (557 – 641 AD). The second is in the style of the Yuan dynasty official, painter, and calligrapher Zhao Mengfu (1254 – 1322 AD).

The nature of the written Chinese language enables it to say more using less space. Each character or pair of characters is an entire word.

For example, here is the same sentence in English and Chinese:

Grasp the meaning but forget the words

知道了意思而不再记得言词

Classical Chinese (the version used for writing by the educated elite up until the 20th century) is even more impressively concise. The above sentence is written:

得意而忘言

And, of course, not only is classical Chinese remarkably ‘efficient’, it also happens to be a storehouse of great philosophy and literature. There are thousands of great writers’, poets’, philosophers’ words to choose from. Here are just a few random samples:

人之生也直宕之生也幸而免

A man survives by his integrity. If he survives without it, it’s down to luck.

Confucius (c. 551 – 479 BC)

千里之行始於足下

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step

Laozi (born 571 BC)

千人之諾諾不如一士之諤謔

The crowd’s ‘yes’ is not as one decent person’s ‘no’.

Sima Qian (c. 145 – 86 BC)

人生處處知何似,應似飛鴻踏雪泥。

泥上偶然留指瓜,鴻飛那復計東西。

To what should human life be compared? A wild goose trampling on the snow.

The snow momentarily retains the imprint of its feet, then the goose flies away to no one knows where.

Su Shi (1037 – 1101 AD)

養非是如何椎鑿用工只是心虛靜久則自明

Nurturing your mind shouldn’t involve laboriously hammering away at it. It’s simply to keep your mind calm and open so that it will eventually become bright by itself.

Zhu Xi (1130 – 1200 AD)

What implications does this have for tattoos?

In my opinion, the above points lead to the following conclusions:

If you’re going to get a tattoo with Chinese characters, choose traditional Chinese characters over simplified ones.

Have the tattoo written vertically (with no punctuation) rather than horizontally with punctuation.

Choose a calligraphy style (regular, running, grass, seal, or clerical script) rather than a printed font style.

And once you have chosen a script, you can also consider whose version of any given script you would like.

Finally, if you know what you want written, find a good translator to help you find the best version of it. If you don’t, search ‘wikiquote’ or other resources for something that catches your eye. In either case, go with classical Chinese rather than modern Chinese if possible!

Choice in tattoos comes down to taste. I hope the above points have increased your range of choice in finding a tattoo related to Chinese characters.