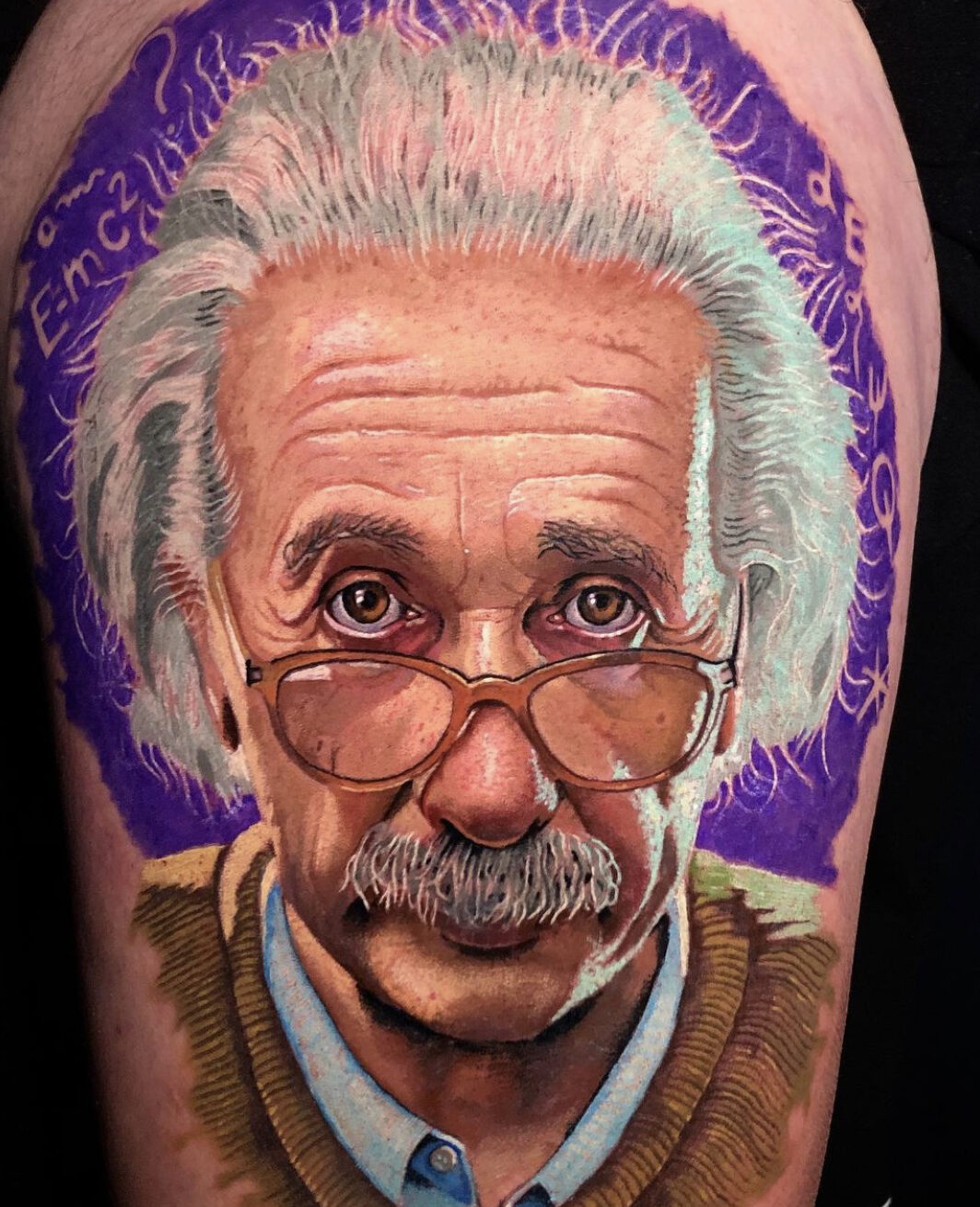

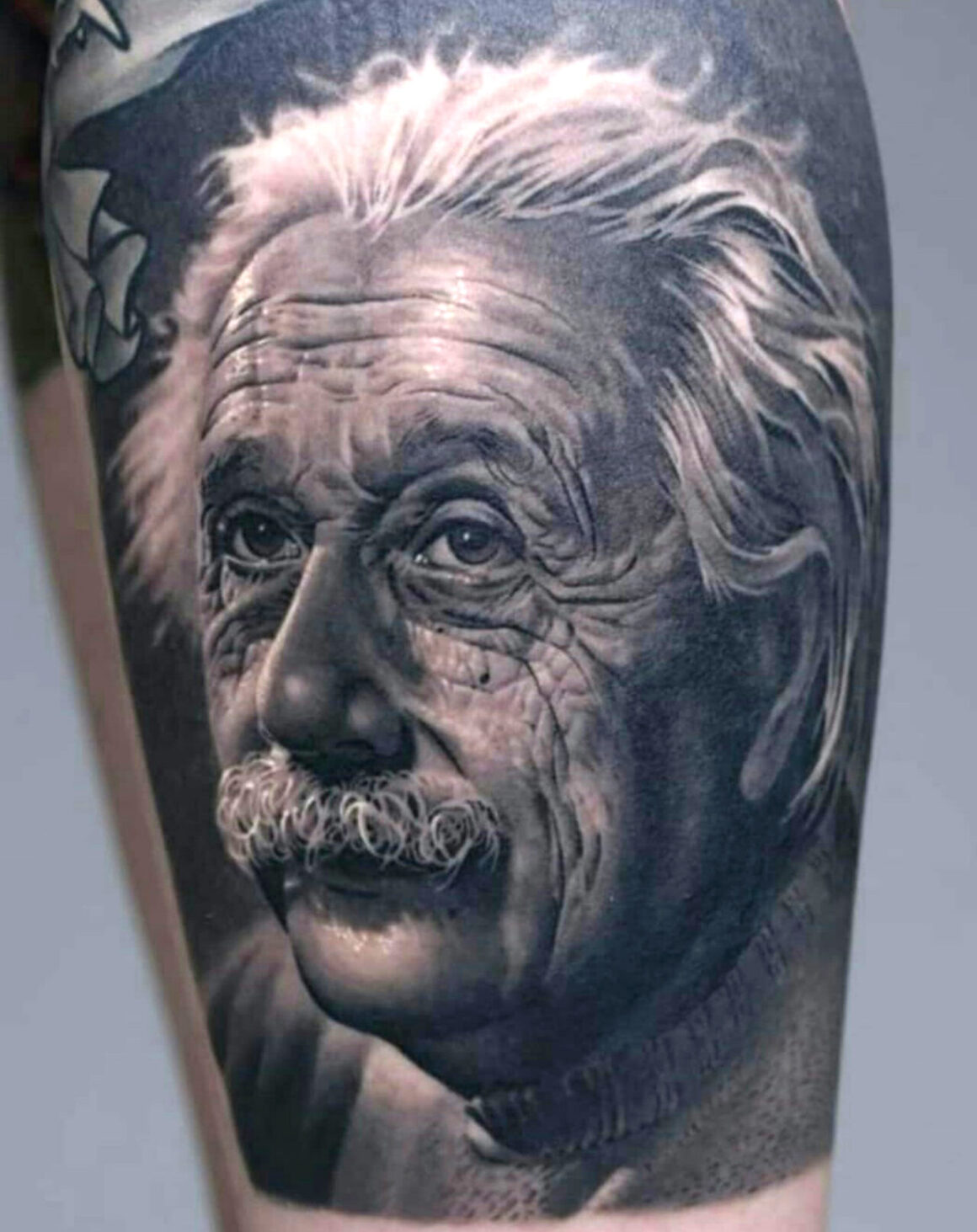

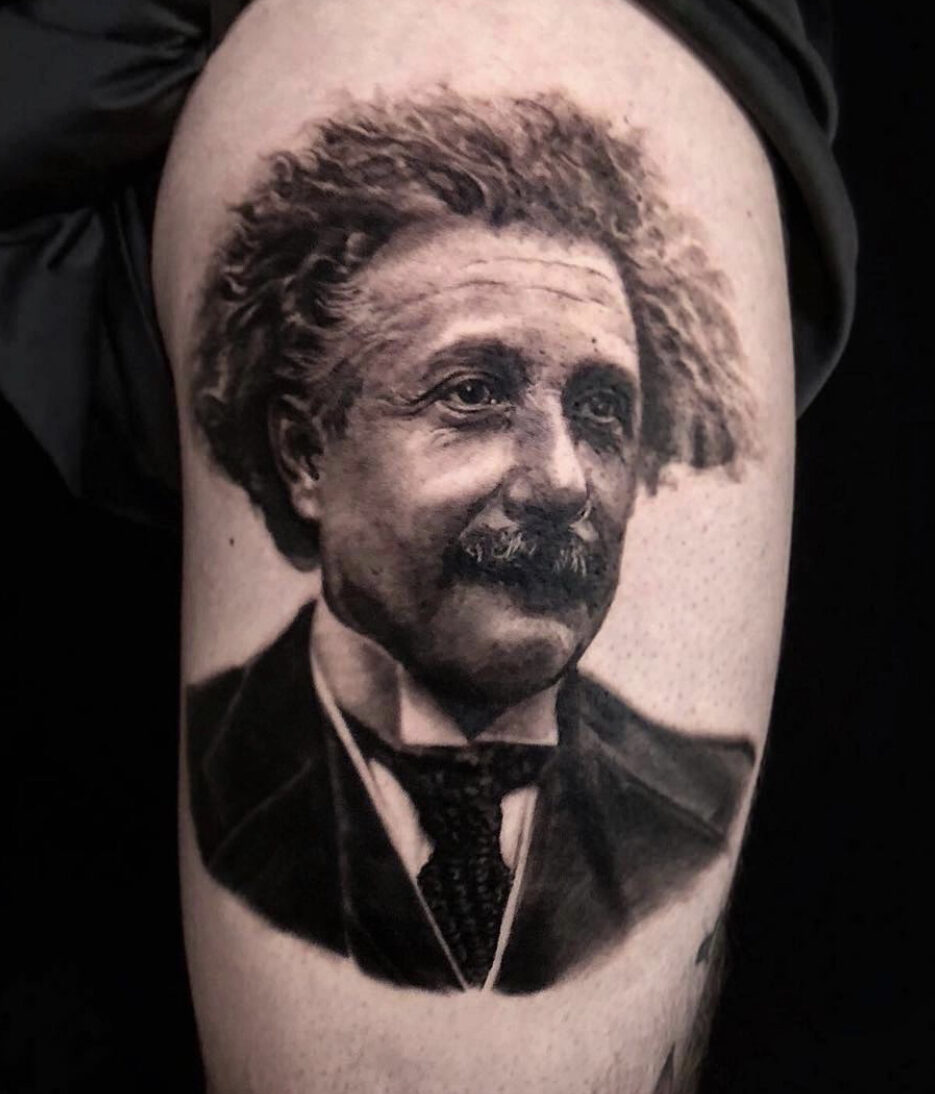

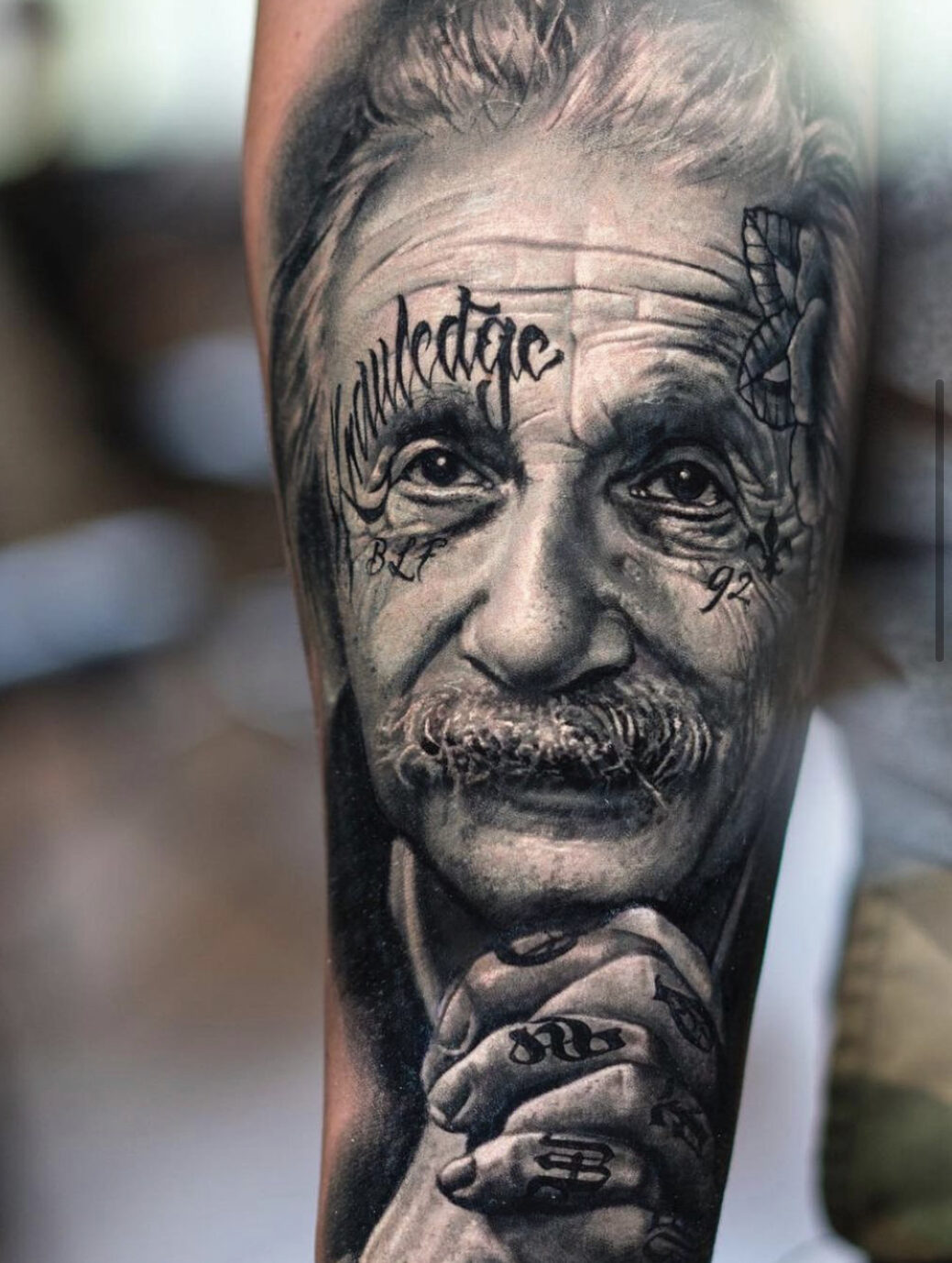

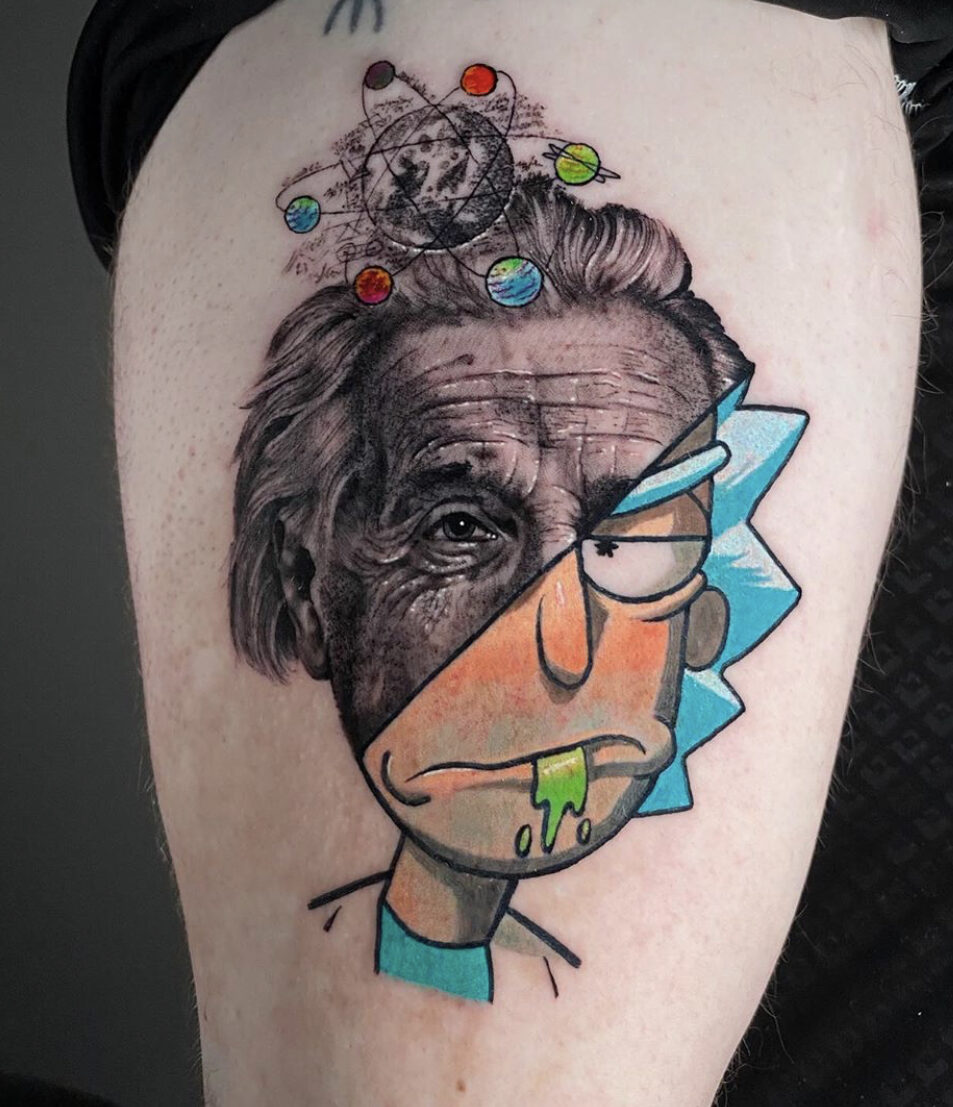

The mastermind of the twentieth century not to mention Nobel Prize for Physics has in recent years become an icon of tattoo art.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was a physicist born in Germany although he became first a Swiss and later an American citizen. He is best known for his mass-energy equivalence formula (E = mc2), the world’s most famous equation, as well as for many other studies of fundamental importance in the field of science.

In 1921, as a brilliant forty-two year old, Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics “for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect”, a pivotal step in the development of Quantum Theory.

He is legendary (in the sense of urban legends) for his supposed failures in his youth in the field of mathematics though the renowned physicist always refuted these ridiculous accusations: “I have never had problems with maths. At 15 years of age I was already perfectly able for differential and integral calculus”.

His many biographies recount how Albert Einstein only moved to the United States in 1933, taking up a teaching post at the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton.

When at the end of the 1930s Einstein found out that the scientists of the Third Reich were working on the terrible atomic bomb, he put aside the pacifism he was known for and wrote a heartfelt letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt urging the United States to carry out extensive research in order to beat the Nazis in the race to build the weapon.

Einstein never took part in any way in the Manhattan Project, but in the decades to follow, he bitterly regretted his role – from the sidelines, as it were – in the development of the atomic bomb. In fact, he apologised, drawing up with the philosopher Bertrand Russell what was to become known as the Russell-Einstein Manifesto in which the two great thinkers of the twentieth century, in the most straightforward and simple manner, asked all the governments of the world to “find peaceful means to settle the differences between them”.

On his death in 1955, Albert Einstein expressly requested that his body be cremated. Thomas Harvey, the pathologist at Princeton, had other ideas however and during the autopsy removed his brain which he then sectioned into 170 pieces which were carefully preserved!

Harvey had not received any medical authorisation and was formally accused of “theft of a brain”. The organ was therefore given back to the family and heirs of the physicist from Ulma who, rather reluctantly, changed their mind. Which meant that other pathologists could go on to examine it in an attempt to discover the origin of the extraordinary intelligence of Albert Einstein. Not that any study ever brought to light anything of significance in this regard.